Introduction

One of my favorite investors up until now is Nick Sleep. He ran the Nomad Partnership from 2001 to 2014 and achieved excellent returns (20% CAGR).

When reading through his partnership letters, you can see how he evolves as an investor, at first, looking for undervalued companies and special situations (like investing in Zimbabwe) until gradually honing in on high-quality companies to hold on for the long term. (I think he still holds Amazon and Costco to this day).

Nick Sleep popularized the term destination analysis in his letters. (if you haven’t read them, please do, you’ll learn a lot and they are excellently written). My goal is to perform such an analysis in order:

To paint a picture of where Dino could be going in 20 years

To get to a better understanding of the business, to get to the DNA of the company

To identify what management can do to get there in the future (for example are they perhaps sacrificing short-term gains to benefit their long-term destination)

To see the risks, what could prevent the company from reaching its destination

To evaluate if Nick Sleep would buy the company

To avoid getting into a theoretical discussion, we’ll use the company Dino Polska as an example. This article will give a brief overview of what kind of company Dino Polska is, but without going into too much detail. I’ll link to other resources that already covered this at the end of this article. The main focus here is the destination.

The order of things

There is a certain order to follow when analyzing a company. The destination analysis should come last.

Why?

Because it can be too compelling. The human brain can paint an incredible picture and narrative that could lead you into action. Before doing a destination analysis, it is important to conduct a fundamental analysis of the company’s accounts, its past performance, how it is leveraged, etc.

The destination analysis should be the last step.

Walmart: Back in time

Before diving into Dino Polska, I was reminded of a question my professor in finance asked me a long time ago. He said:

If you had invested in Walmart in the 70s, would you have done okay all these years later?

At the time, I had no idea, I wasn’t investing in the stock market yet.

The answer is of course a resounding yes. But then he asked:

Why didn’t people just buy Walmart and hold on to it?

In hindsight, it might seem obvious, and even if you had bought in the 2000s or later, you still would have made a great return. This of course goes back to the lessons from books like 100-Baggers and 100 to 1 in the stock market where the big difficulty is to hold on to your investments for decades.

But by going through the biography of Sam Walton, I noticed, in the early days, it wasn’t that of an obvious choice. Walmart was out of the norm. It was a small and nimble speedboat. We all take retailers and discounters for granted now.

Sam Walton was someone who not only introduced new concepts but took up new ideas and implemented them vigorously:

He introduced the concept of a discounter: selling at 80 cents instead of a dollar but selling 3 times as much in volume

He changed his classic variety store (where you go to the counter, and you ask someone what you need who will get it for you) to a store as we know it now (where you walk around and shop, until going to the checkout)

He developed his own supply chain and distribution centers to reduce costs and increase margins

And finally, only in 1988 did they add groceries to Walmart’s offering through its supercentres. (which means reinvesting and adding a cold supply chain)

He was someone who experimented, to fail fast. He embraced technology (they had their satellite network in the 70s, but oddly missed the internet) to get the sales numbers as fast as possible and share them with all the store managers. He wanted the feedback loop the be as short as possible so that he might learn faster than the others. He was frugal: the name Walmart was proposed by a friend who said: If you take the first part of your name, and mart, its only 7 letters, you’ll save on the cost of the neon signs above all the stores!

And finally, his best trait, he always went on the ground in other stores, to see what they were doing better.

All this together, Walmart, who was the disruptor, put K-Mart, the incumbent out of business by focusing on lower prices and a hyper-efficient operational excellence model. K-Mart was too big to pivot. (at a certain moment, Walmart only had 5% of K-Mart’s revenue)

Who is Dino Polska?

Dino is a food and non-food retailer in Poland with currently about 2300 stores. It was founded in 1999 by Tomasz Biernacki and IPO’d in 2017. Dino is a vertically integrated business. It has 8 distribution centers which each can serve up to 350 stores, and a lorry fleet. Their meat processing plant provides fresh meat to the stores and reduces spoilage. All stores are owned by Dino and built by a separate construction company that is owned by the founder but not integrated into the company.

Dino builds its stores, that are smaller (400 m2) than its bigger competitors and targets rural and suburban areas where there is a less dense population.

Past performance

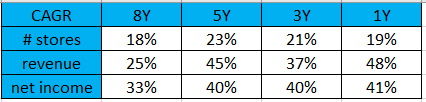

Past performance has been stellar. Here are the different CAGRs for the last years:

But based on H1 2023 results, growth is slowing down. The number of stores growth should be double digits but more in the lower range. Past growth rates may not be representative of what the future holds.

Capital allocation

Dino has never issued dividends or did buybacks. It has reinvested all capital into organic growth by opening new stores. It has recently made a small acquisition of an online retailer. Management has stated that they want to continue focusing on growth which if possible is the best form of capital allocation. Dino has a return on invested capital exceeding their cost of capital and is creating value.

The retail market in Poland

Based on 2022 sales figures, here are the TOP 4 retailers in Poland:

Biedronka: 79 billion

Eurocash: 30 billion

Lidl: 27 billion

Dino 20 billion

With Auchan, Kaufland, and Carrefour all competing for the fifth place in the 10 billion Zloty range.

It must be emphasized that Dino held the 8th place in 2015. In 8 years, it has grown revenue from 2.6 billion to almost 20 billion Zloty and is still growing.

It should be possible, in time, to get to the number 2 position in Poland where a stabilization in the market could occur with the 2 biggest competitors being Biedronka and Dino Polska.

Management

Dino is owned by Tomasz Biernacki (51%). From Forbes:

So it is difficult to find a lot of information on him. Because Jeff Bezos had a lot of similar traits to Sam Walton, I would have loved to have a deeper look into the chairman of Dino Polska.

There are 3 traits I have found that are similar to the 2 greats in business:

Failing fast: Apparently, Tomasz experimented a lot in the early days of Dino to find the right niche. Although at the current iteration of Dino, I haven’t seen a lot of evidence of this protruding throughout the organization

Frugality: He has this reputation and was famously involved in picking the lowest-cost basket maker for garbage collection at the stores.

Long-term: Based on what we know, Dino is focused on growing for the long term. One piece of evidence is the fact that they insist on owning and building their stores. Sorha Peak calculated that the time it takes you to start seeing a benefit from owning versus leasing is 9 years. Since their goal is to be around for a lot longer than that, it seems like a good long-term choice.

There is no CEO at the moment, and for the time being, they are running the company as is. The management team has a lot of experience and is all internally promoted.

There is no shareholder incentive program.

Management is paid in cash on a fixed and variable basis. Their fixed salary cannot exceed 10 times that of any employee in the company. Bonuses are based on annual net income.

Dino is not Walmart

Dino is not Walmart. Dino is not Costco. It is its specific value proposition.

Like Walmart, Dino’s focus is on rural and suburban areas. Their stores are ‘small ’ and built next to small towns. They only need 2500 people to make a store profitable. Although they are a discounter, convenience comes first.

The Myth of Excellence

An important aspect of supermarkets is their cash flow. When you buy at the store, you pay when you leave. But the supermarket doesn’t pay the supplier immediately. They’ll always have a window of cash available, it’s the magic of negative working capital.

Supermarkets are all about scale. Scale means more leverage to negotiate with suppliers. Margins are typically low so scale means an increase in absolute numbers.

These are the basic principles of the business model of a supermarket. Companies compete by differentiating their value proposition. We can identify :

The discounter competes by providing the lowest price

The hypermarket competes by providing an abundance of stock and wares

The smaller stores compete on convenience instead of price

Price, convenience, and assortment make up the holy trinity of retail.

There are other examples where certain supermarkets treat customers like kings, the more royal customer treatment, with of course higher prices. But for the sake of simplicity, let’s keep it at the 3 categories described above.

DINO doesn’t fit clearly in any of the above 3 categories. It’s rather unique.

Those of you who have read the Myth of Excellence will say: Then they are leaving money on the table! If you’re the best in both, you’re leaving money on the table.

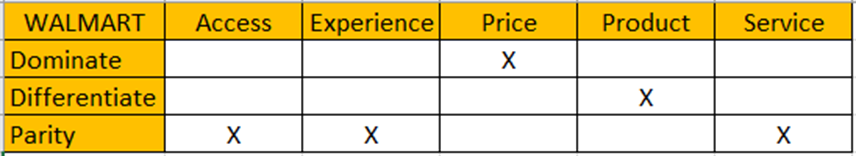

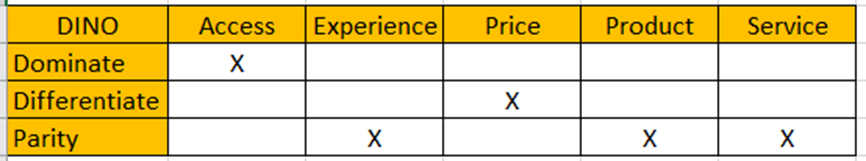

So a quick reminder, the customer relevancy model allows us to quickly differentiate between a company’s strategy. We can define 5 attributes :

Access or in this case convenience or proximity

Experience of the customer

Price

Product in the case of a supermarket, the range of products and quality offered

Service customization to the needs of the customer

Walmart’s slogan was: Always lower prices, always.

You go there to get name-brand products or private labels at the lowest prices and a massive assortment. However when looking at the founding story of Walmart, because they wanted people outside of the cities to experience a retail experience, just like you have in the cities, the model has shifted with the years.

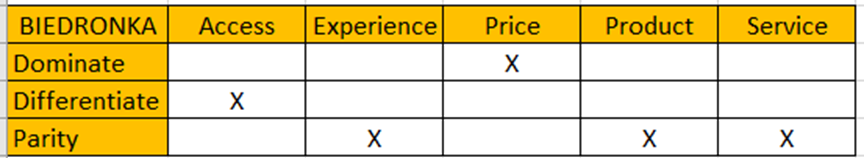

DINO’s main competitor in Poland is a company named Biedronka. Its slogan is codziennie niskie ceny which means: “everyday low prices”

Their model looks like this:

DINO's focus is on access and price.

Its market line is Najbliżej Ciebie which translates into “Closest to you”.

So DINO’s selling proposition is convenience. But this does not make it unique. There are lots of mom-and-pop convenience stores in Poland that are located nearby.

What DINO does more, is provide low prices. (they actively lower prices compared to competitors for about 500 SKUs in their stores) and a full assortment (5000 SKUs in total).

Both DINO and Biedronka have been very successful over the last decade in Poland. A low price and convenience are what the Polish customers want, which partly explains the success of both companies.

International Expansion

What are the conditions in the surrounding countries? As we discussed before, Dino, with its unique value proposition and scaling capabilities, can take more and more market share in a fragmented market in Poland. Mom and pop stores disappear and Dino benefits.

The market in Poland:

Is fragmented, a lot of small stores

Is rural, most people live in small towns

GDP per capita has increased over the years

It will keep increasing but at a slower rate

The population will decline in the future

In other words, Dino competes in a growing market.

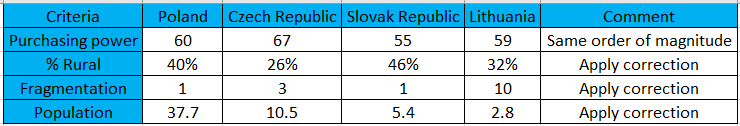

What does the market look like in the other countries? Here are different data points:

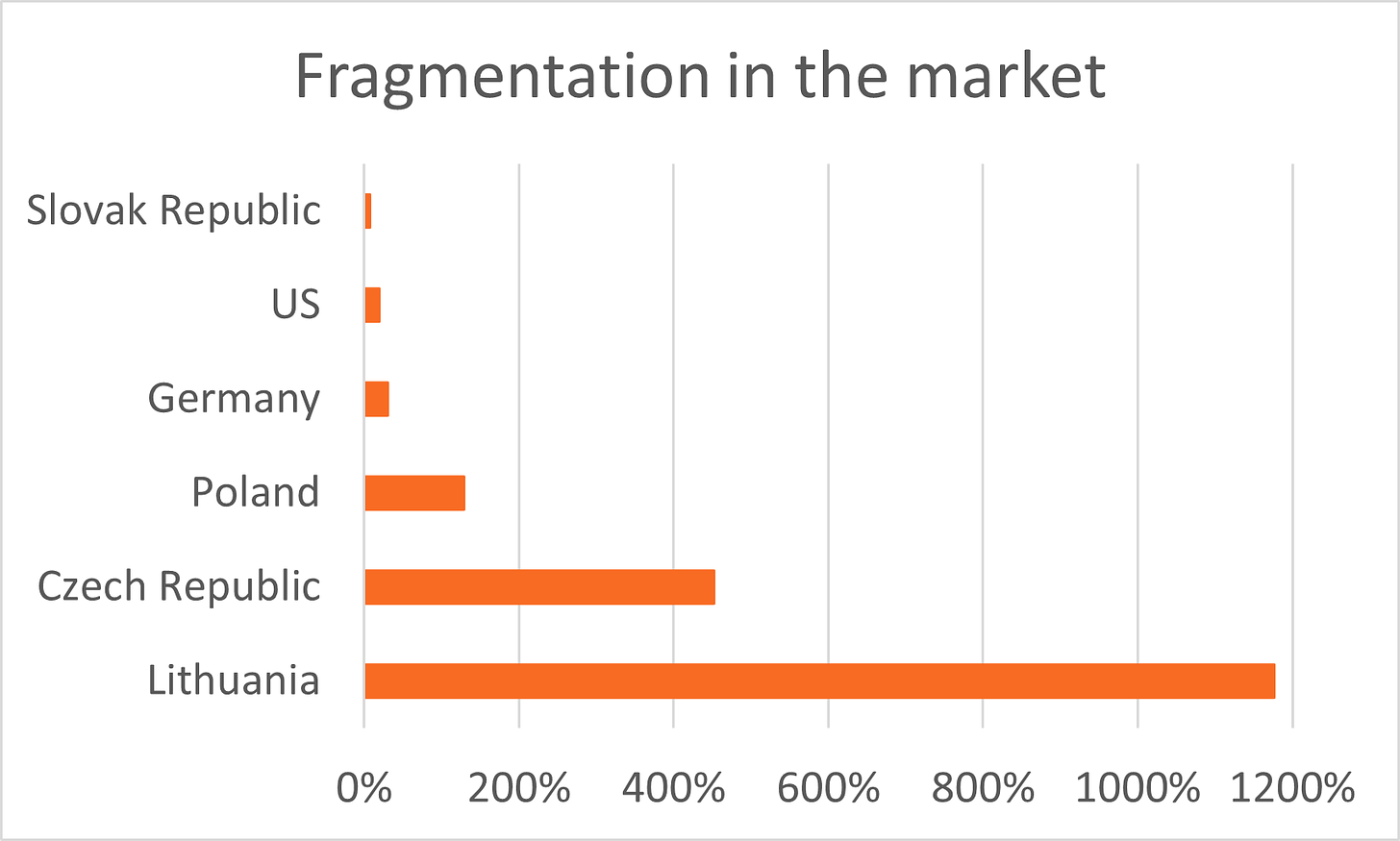

Is the market fragmented?

To make a comparison of how concentrated the markets are, we retrieved the number of registered grocery businesses per country and divided them by their total population. To emphasize, it is the number of businesses, not the number of stores. But it gives us an idea of the number of mom-and-pop stores per country.

The higher the number, the more fragmented the market. We’ve added Germany and the US for comparison as those are fully developed markets.

Conclusion: Lithuania and the Czech Republic are more fragmented than Poland and could provide Dino with a market opportunity. We are unsure of the data for the Slovak Republic. The same data provider shows that there are only 380 grocery businesses registered for a 3.3 million population. This seems too low. I would need to find additional data to challenge this.

Purchasing power

Let’s take a look at the purchasing power in the different countries compared to the United States and Germany. We’ll use data from numbeo.com. Purchasing power on itself gives us a first clue but we’ll add a second data point, the grocery index.

Here are the definitions:

Grocery Index: This index provides an estimation of grocery prices in a city relative to New York City. Numbeo uses item weights from the "Markets" section to calculate this index for each city.

Purchasing Power Index: This index indicates the relative purchasing power in a given city based on the average net salary. A domestic purchasing power of 40 means that residents with an average salary can afford, on average, 60% fewer goods and services compared to residents of New York City with an average salary.

These are relative indices compared to New York City. So if we want to combine both, you want the grocery index to be as small as possible and the local purchasing power to be as high as possible. Here are the results:

Germany is the big winner because compared to New York, groceries on average only cost half and they have the same level of purchasing power on average as someone living in New York City. When looking at the countries neighboring Poland, in purchasing power (excluding Ukraine) they rank 2nd after the Czech Republic but groceries are cheaper.

Although we can conclude that Lithuania, the Slovak, and the Czech Republic are in the same ballpark as Poland, beware that these are averages. Local purchasing power varies within each country, as well as the price of a basket of goods (up to 30% within Poland based on the study by Sohra Peak Capital).

It might therefore be a good idea to look a little bit deeper into the rural versus urban differences.

Oh, and as you probably already know, New York City is expensive.

Do people live in cities or towns?

Because Dino has such a small capture area, they only need 2500 people, and because Dino’s focus is outside of cities and towards small towns, let’s take a look at the percentage of rural population in the different countries.

Before arriving at any conclusion, a caveat. How does the World Bank derive rural population data?

Rural population refers to people living in rural areas as defined by national statistical offices. It is calculated as the difference between the total population and the urban population.

And more importantly:

The rural population is approximated as the midyear nonurban population. While a practical means of identifying the rural population, it is not a precise measure.

Based on this, what we can do however is look at the evolution per country and try to draw more general conclusions.

The fact that the United States and Germany have evolved towards more urbanization is not surprising and seems realistic. When disregarding Ukraine for the moment, all the other neighboring countries are trending in practically a straight line.

Although Poland is the less Urbanized of the lot, if we compare the countries to their fully developed counterparts, Germany and the US, they are a lot more rural and thus could provide opportunity for Dino.

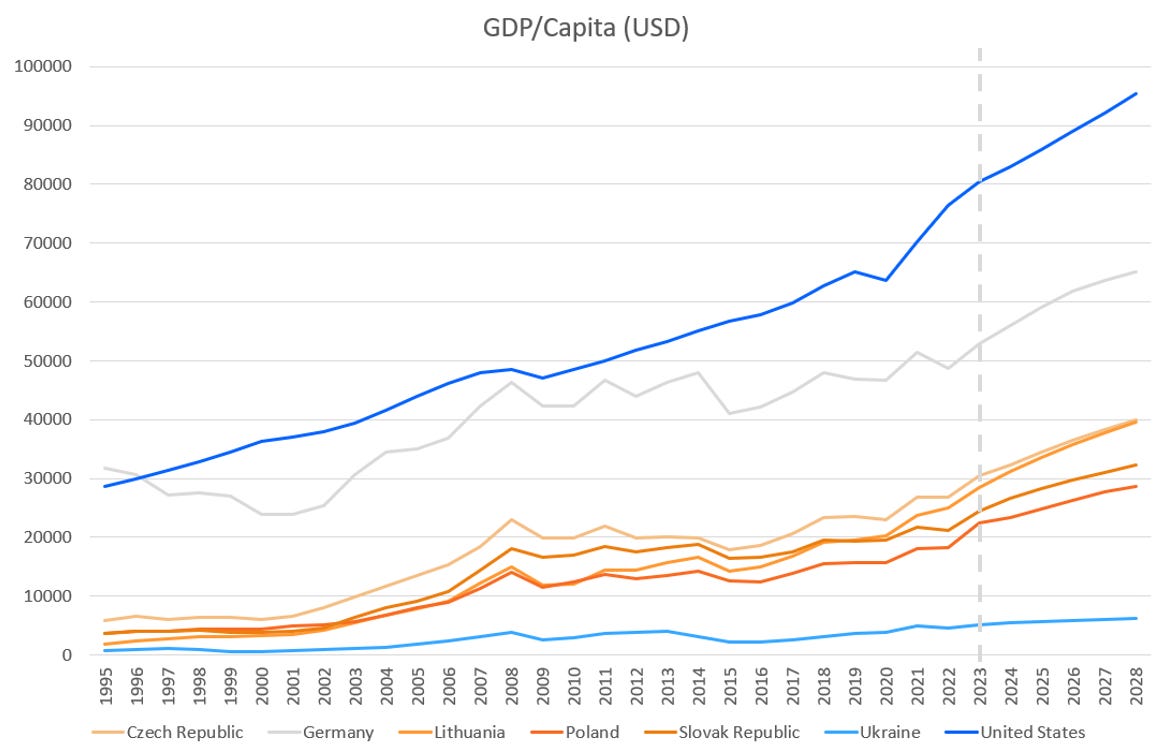

How is GDP/Capita evolving?

Here’s the data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF):

In blue, we see the two outliers, the United States and Ukraine. The orange tints show Poland and its direct neighbors, where all these countries are steadily growing. Finally, Germany sits between the US and the rest.

What surprised me were the projections for 2028 by the IMF. All countries, except Ukraine, are foreseen to increase their GDP/Capita, but the US should increase at a faster rate.

Not what I would have expected.

The destination

Let us first look simply at how big Dino could become.

Can Dino Polska 100x in size?

This would mean sales being 500 billion USD. The current PPP GDP of Poland is estimated at 888 billion USD and is expected to increase at a rate of 2% per year. Walmart which is the biggest retailer in the world, had global net sales of about 611 billion in 2023.

As production output GDP/Capita increases, so does the average wealth per capita and the part of the budget spent on groceries. So there may be tailwinds, but it will not be enough.

Conclusion: it is unlikely that Dino Polska will be able to gain 100x in size on revenue, even in 20 or 30 years. It would then need to become the dominant retailer in Europe similar to what Walmart is right now in the US.

Can Dino Polska 10x in size?

It becomes more plausible. Let’s see.

In pure number of stores, we are talking 23 000 stores which is not likely.

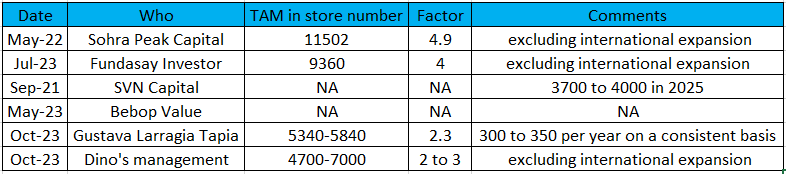

Before going into our estimate for what the upper limit is, here are some other estimates that I found. I’ve included the date of publication because an estimate is only true at a certain moment in time.

The factor is the multiple increase from the current number of stores.

Information on Dino’s management comes from notes taken by Galileo Capital (X handle @pedroleongarci2) who claimed they interviewed Dino’s management. I cannot confirm the accuracy of this data.

Links to all the wonderful articles can be found at the end of this publication.

What we know is that Dino had an internal target of increasing the number of stores by 20% and that a store reaches maturity in about 3 years. Management has said the store growth in 2023 will probably be below that 20% and we can already see it based on the H1 2023 results. In any case, it would not be possible to maintain a 20% increase in stores year over year as this would mean that at a certain moment, they would be building 1000 stores per year.

Based on:

Increased competition domestically with Biedronka who has also launched their own Dino-style stores (about 148 stores in 2021)

A current growth slowdown (H1 2023 results)

And the latest information from management

I would estimate the upper limit of Dino stores within Poland to be between 6000 and 7000. This also fits within the TAM calculation made by Sohra Peak Capital which should be the theoretical upper limit without taking into account dynamic market effects and competition.

Now to add the international opportunities. Based on the previous analysis of neighboring countries, I estimate that expansion should be possible towards Lithuania, the Slovak, and the Czech Republic.

Based on pure population numbers this would add 50% to the TAM. Taking into account the previous elements:

Purchasing power

Rural distribution of population

The fragmentation of the market

I would apply the following calculation to the TAM:

When linearly correcting for these parameters and adding the international TAM to the TAM in Poland, this leads to a 22% increase in the total potential market.

On a 6000 to 7000 store basis in Poland, this would mean a total store number count of 7200 to 8500 stores.

Going international is hard. Walmart at the moment has about 18% in revenue outside of the US and it hasn’t always been a success story. Although, based on the above analysis, there are a lot of similarities between the mentioned countries.

Conclusion: even 10 times in size seems impossible. The total long-term number of stores is estimated at 8500 stores. The speed at which the stores will be built at the moment seems to have capped. I would estimate a rate of 300 to 350 in the coming years but not more. This would mean that in Poland, saturation would be reached in about 14 years although, in reality, it will take longer because, in the end, fewer and fewer stores will be added. Domestic saturation will probably be met in 2 decades.

Online retail and grocery delivery

Dino recently acquired a 75% stake in eZebra, an online non-food retailer in Poland focused on cosmetics and medicine for 14 million USD. Dino was planning to develop their online capabilities in-house but it may indicate they want to jump-start the process.

Regarding Dino’s destination, how will online retail in Poland impact Dino’s business?

Amazon has been active in Poland since 2014. However, Amazon has not yet cracked the code in the grocery delivery segment. Even in a fully developed market, grocery delivery is still a small part of total online retail but is expected to grow.

In the short-term, this should not impact Dino’s business specifically because they focus on convenience and price and the customer is price sensitive.

Online grocery retail, in Poland and neighboring countries for people living outside the cities can only be a success if:

The price is lower

The assortment is wider

They can provide convenience and nail the delivery

It always comes back to the holy trinity of retailing. To reach the holy trinity you need scale (remember Amazon’s e-commerce was for a long time not profitable, they managed to succeed partly thanks to AWS who compensated). Therefore, the only company at this time I see cracking this code, but not in the short term is Amazon.

In the end, if Amazon can implement this, the impact will be bigger on Dino’s competitors because Dino focuses on convenience.

My local supermarket is a 10-minute walk from my home. I would never order groceries for delivery, I just do not see the benefits, but things could always change rapidly and I might be proven wrong.

This segment should see an increase according to estimates of 2.5 billion PLN in 2023 with an estimated CAGR of 15% to reach 1 billion USD in TAM in 2027.

This may come true, but I honestly think it will not matter because of Dino’s value proposition. If in 20 years, you live in any town in Poland, and you have a Dino store within a walking or a short riding distance, I do not see people bother to order a grocery delivery at home. The only reason they would do it is if it is cheaper.

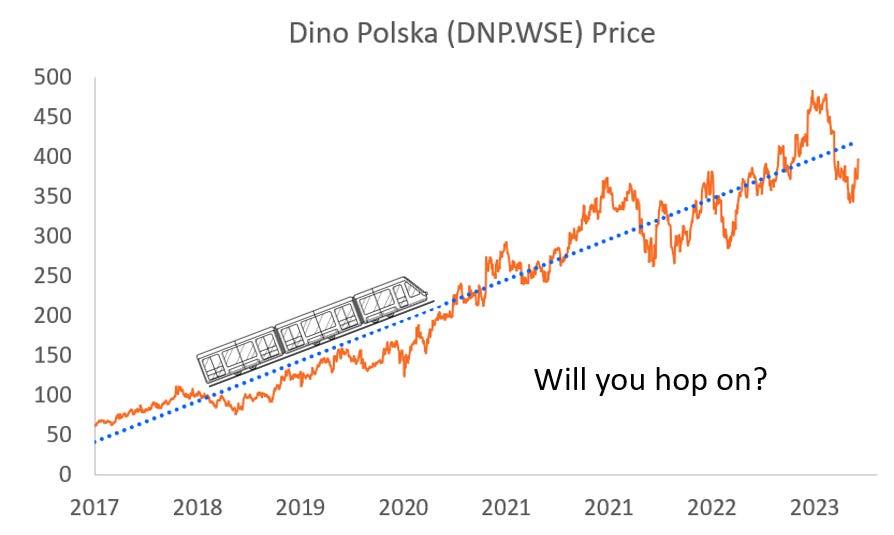

Pricing and Valuation

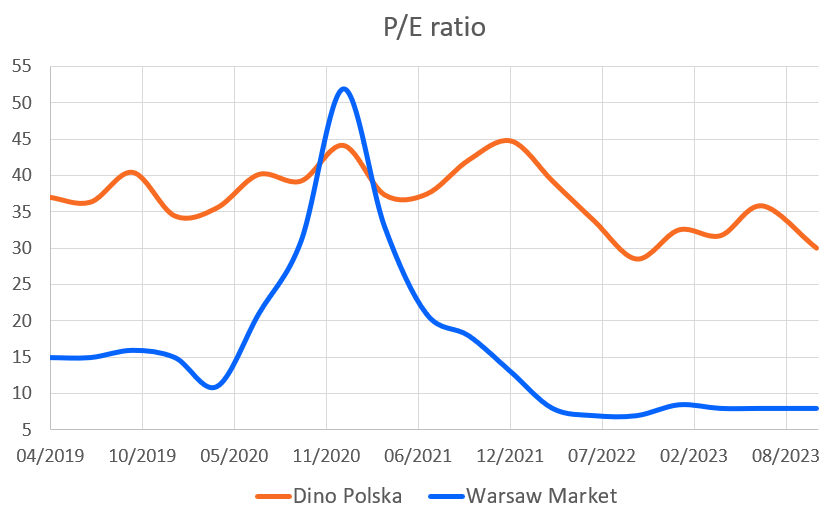

I’m not going to provide a full valuation here. I’ll reserve that for a future full deep dive. But looking at the price in the market, Dino has never been çheap looking purely at P/E ratios. As we discussed earlier, we have to be careful with them.

Dino has never traded below a PE of 25 and the difference is startling when compared to the entire Warsaw market:

A Walmart you could, have bought at a PE of 10 throughout its history numerous times.

At this moment in time, the business model of a great retailer is well-known by most investors. The information is widely available and since Dino is growing at a rapid pace, the market attributes a high multiple.

You will not have the twin engine of growth of your investment. There will not be a multiple expansion. In fact, on the opposite lies the greatest risk, the risk that when growth slows down and Dino starts to mature, multiples might come down also.

This is not the case for current supreme retailers such as Walmart or Costco but has been the case for other retailers in Europe.

I took a position in Dino because I consider it a great business at a fair price and if I can hold on to it for the next 2 decades, it will probably do ok.

Nick Sleep

At the start of this article, we listed the following goals:

To paint a picture of where Dino could be going in 20 years

To get to a better understanding of the business, to get to the DNA of the company

To identify what management can do to get there in the future (for example are they perhaps sacrificing short-term gains to benefit their long-term destination)

To see the risks, what could prevent the company from reaching its destination

To evaluate if Nick Sleep would buy the company

I want to end here with the last question:

Would Nick Sleep buy Dino Polska?

I think not, and here is my reasoning.

Dino has an outstanding business model, but not the best business model. I can best explain it through analogy:

Amazon and Costco have the scale economies shares model. Through scale, they increase in power, but by giving away a part of that power to its customers, it scales even more, and you create a chain reaction. Amazon also has the optionality, the experimentation which eventually could lead to other businesses (for example AWS).

I would compare Dino more to Southwest Airlines. The retail industry is a better industry than airlines. But Southwest (and Ryanair in Europe) choose to be very specific in their strategy:

Only short routes

Standardized fleet

No frills

Low prices

Convenience

Exactly what DINO does in Poland.

The second reason is price. Although a long-term view diminishes the impact of the price you pay, except maybe for Amazon, Nick hasn’t bought these companies at a level of PE that Dino is trading.

Conclusion

After putting many hours into this analysis, it seems I’ve barely scratched the surface. This article will be updated in the future with additional research I’ve conducted.

Dino Polska is a high-quality company trading consistently at a high price in the market. In the retail market, it has positioned itself as a proximity discounter with a full assortment of mainly foods and non-foods. Due to its low capture area of 2,500 people, it can go where other retailers are not. It is vertically integrated by processing its meat and owning its distribution centers and stores.

Almost all stores are owned and built by a specific construction company created by Dino’s owner and chairman for that purpose. The number of shares has remained stable since the IPO in 2017 and no dividends are paid. Dino reinvests as much as possible into organic growth and opening up new stores each year.

Dino tries to reduce costs by solar power, increase revenue streams by adding postal services, and in the future maybe gas stations.

In the coming 20 years, Dino will keep growing its store count up until we believe a maximum of 7000 with an additional 1500 internationally if it decides to do so.

The question is not if they will expand abroad, but when.

Management has already stated that they see the opportunity, but for the moment are focusing on Poland. Is this the right decision?

Dino is not the next Walmart or Costco. It is its own thing, a fabulous example of strategic positioning and flawless execution.

What Dino has is a form of predictability, what it lacks is the optionality of a surprise return, an event like Amazon with AWS that would suddenly propel the company further.

Dino is like a train, rolling along, heading towards a great destination.

Will you hop on?

—---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In my research, I have come across many articles by others who are referenced here.

Sohra Peak Capital Dino Polska thesis: the best analysis of Dino Polska out there, period.

Colossus business breakdown with Jon Cukierwar: same thing but in audio format

SVN Capital Article on Dino Polska: provides great little insights about the chairman and Dino’s business

Substack by Fundasay investor: Provides a complete overview and looks to the future, you should subscribe

Substack bebop value: Great write-ups on UK and Polish companies. Recommended

The next Walmart by modern investing: You source for other articles about Poland

Acquired podcast on the history of Walmart: A must-listen if you’re studying retailers

and I’ve probably forgotten a lot of others…

One more estimate for your table: Shree says 5,300-5,500 domestic stores here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OXYwcYNkdnM&t=793s , and he repeated the 5,300 number in a recent interview with CompoundingQuality.

Nice writeup btw (yes, time-consuming indeed! I've spent my fair share on this company). I like the Nick Sleep angle of asking "what could stop this company from reaching its destination." I suppose that would be how fast Biedronka expands with its small store format into small towns (needs to be monitored).

The share price can definitely 10x or even 100x, it doesn't really matter that the number of stores has an upper limit. They could do share buybacks and eat away 5% of shares every year once they reached the store limit. Or they extend the product line by adding something like fuel stations, storage containers or fast food restaurants into their stores. Also the asset value will be significant, they will be one of the largest owner of property. I see the most likely expansion country is Ukraine (after the war ended) because it has similar rural structure and large population and country size.