A 10-step checklist you can use to evaluate management capital allocation to make better investment decisions

Introduction

Most CEOs are bad capital allocators according to Warren Buffet.

Most investors are bad capital allocators based on their investment performance according to JP Morgan.

Let’s take a look at what capital allocation is and how we can verify if a management team is doing a good job or not.

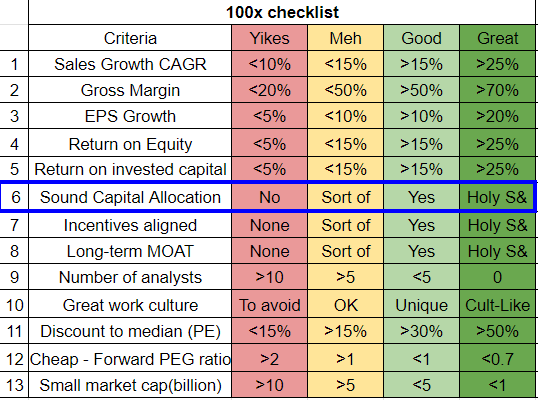

100-bagger checklist

A couple of weeks ago we introduced the 100-bagger checklist. You can download it here. Previous articles discussed step 5 ROIC and step 11 the P/E multiple.

The time has come to dive deeper into how we can asses the capital allocation strategy of a company (step 6).

What is capital allocation and how can we evaluate it?

The one-dollar test

The objective of capital allocation is to build long-term value per share.

Capital allocation is the CEO’s most important job - William Thorndike.

Capital allocation is equivalent to what we do as investors. You have an income, cash is coming in and you spend, cash is going out. If both are equal, then there is no excess cash. The only decision you need to make is to figure out how to increase cash coming in or decrease cash going out so that you have excess cash.

Life is great!

Or is it?

Maybe you want to build up some cash. Create wealth. Be financially independent?

Somehow, you manage to increase cash coming in or decrease cash going out. Maybe even both at the same time. Now you have excess cash.

What are you going to do with it?

Buy a house?

Buy a car?

Buy a stock?

Buy an index fund?

Buy some crypto?

I could make a very long list. Every investment you make will generate a certain return (or loss). But will it generate more than your initial investment compared to every other possible investment you could make?

This is the basis of capital allocation. Which investment, at any given moment in time, will generate the best returns?

A CEO or CFO, or you as an investor, have to make the exact same decisions.

Before diving into the possible capital allocation or resource allocation decisions, there is one important test to consider.

In order to know if value is created, companies need to pass the one-dollar test. One dollar invested needs to create more than 1 dollar in the marketplace. The net present value (value discounted to the present) is worth more than the value that was invested.

Passing the one-dollar test means the company has a return on invested capital (ROIC) greater than its cost of capital (WACC). It has a positive spread.

Remember Inmode from the previous article:

Yes, Inmode has passed the one-dollar test in the past. It has created value. But does it have a good capital allocation strategy?

Skip to the conclusions if you want to know the answer.

When someone rises up within the ranks of a company and becomes the CEO, that person usually has significant experience in operations or sales. Capital allocation is not something you necessarily learn when climbing up inside the organization.

Each company is in competition with the other. A company that is a master capital allocator will win over a company that is destroying value. Capital allocation is closely related to the strategy the company has. Strategy is all about how the company is positioning itself in the market. When someone becomes the CEO, usually, the strategy is already in place.

What matters is not the absolute value of ROIC, what matters is how it has changed in the past. Or, what is the expectation for changes in ROIC looking at the future?

One useful measure is the return on incremental invested capital or ROIIC. It displays the relationship between incremental earnings and incremental investments.

where the numbers are the years (0 to 2), IC is invested capital and NOPAT is Net operating profit after taxes.

High ROIICS can fluctuate a lot, so it’s better to take a look at 3 or 5-year rolling returns. High ROIICs mean a company is capital efficient. Looking at historical values can help you in forecasting the future. But beware, do not compare ROIIC to the cost of capital because ROIIC is not a measure of value.

What is capital allocation?

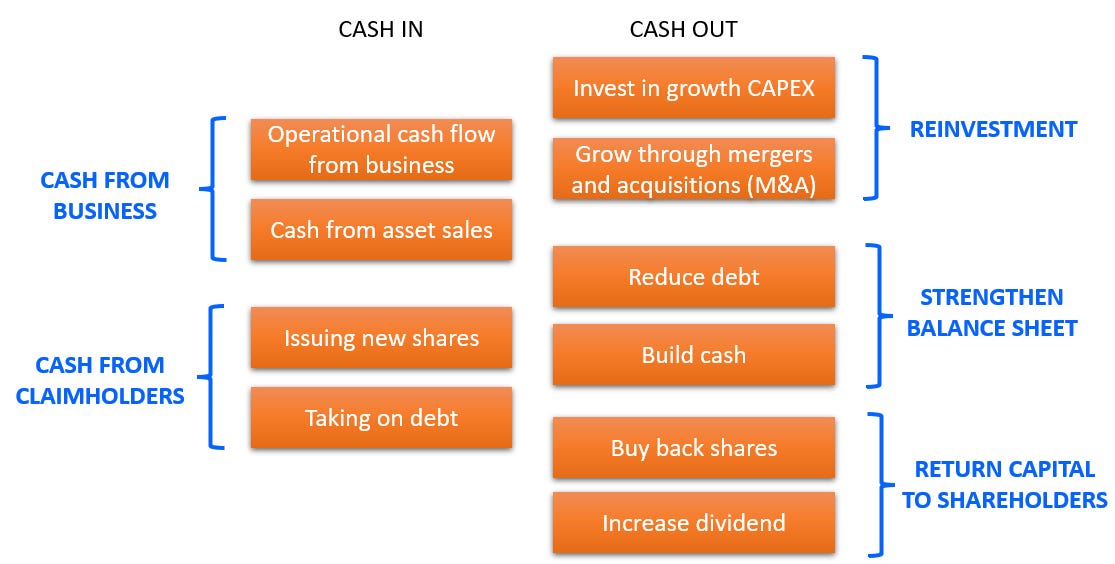

In the end, all possible capital allocation decisions can be summed up as this:

Cash comes in. Cash goes out based on certain decisions.

In summary:

A business generates cash by:

It's business

The sale of certain assets

Issuing new shares

Taking on debt

It can then reinvest this cash to grow its business, strengthen its balance sheet, or return capital to its shareholders.

The management team can invest cash to grow the business. It can perform capital expenditures (CAPEX) to acquire new assets or spend on research and development in the hopes they will generate future excess returns.

If the business has seen rough times or expects rough times ahead, it can decide to strengthen its balance sheet by reducing debt or building up a cash pile to weather future storms.

Finally, maybe no opportunities for growth are available, or balance sheet strengthening is needed, then it can decide to return some cash to the shareholders by buying back shares or paying a dividend.

But then what should the company do? How can it make these decisions in the best way?

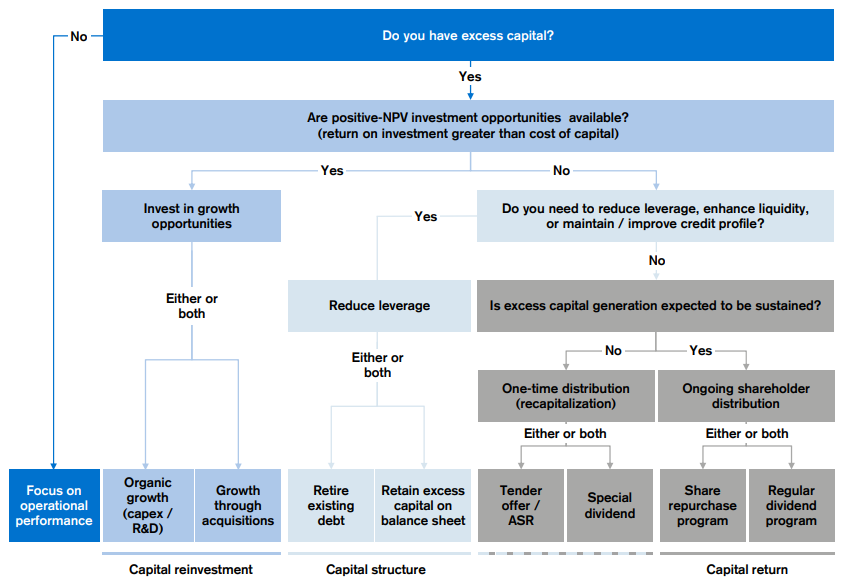

Credit Suisse released a framework that can help:

Let's quickly run through this framework:

The capital allocation framework

Question 1: Do you have excess capital?

If you do not have a cash pile, start working on building one. You have no other decisions to make.

Question 2: Can you spot opportunities for investment that will generate a positive return?

Or rephrasing, do you see investments that can generate a return on capital greater than the cost of capital? (The one dollar test).

YES -> Invest in growth opportunities

NO -> Evaluate the need to strengthen your balance sheet

Invest in growth opportunities

Businesses can spend cash to do research and development or buy new production capacity (CAPEX) in order to grow. Another method to grow is through mergers and acquisitions. Both are capital reinvestments.

If you’re an investor, you’re probably doing this as well. You are taking your cash and investing it in growth opportunities.

Strengthen the balance sheet

This is very specific to the business. Did they have to take on a lot of debt in the past? Maybe it makes sense for them to reduce debt first before reinvesting in growth. Do they have sufficient liquidity?

If none of these are needed, then go to the next step.

Question n°3: Is the excess cash generation sustainable?

In other words, cash is building up, does the business expect this build-up to continue steadily into the future?

NO -> Then you could consider a one-time distribution to shareholders through a special dividend

YES -> Then there are 2 possibilities. Buyback shares or establish a regular dividend program. Or do both.

Now this framework seems extremely logical. If you don’t have cash, try to find ways to generate more cash. If you do have cash, look for opportunities that pass the one-dollar test. If none are available, see if it is needed to strengthen your balance sheet. If your balance sheet is sufficiently strong, see if this excess cash can be generated in a sustainable way. If yes, then look to return cash to the shareholder. If not, look for a one-time return for cash.

The problem with this framework is the following:

“The first law of capital allocation is that what is smart at one price, is dumb at another”. - Warren Buffet

In other words, context and opportunities change all the time. The hierarchical decision tree can be useful but will only sometimes be right. Sometimes, even if you have excess cash, it can be fruitful to strengthen the balance sheet.

Every decision is relative. It has an opportunity cost. But in the end, you need a positive ROI.

Let’s take a look at capital allocation according to past numbers, with some examples.

A history of capital allocation

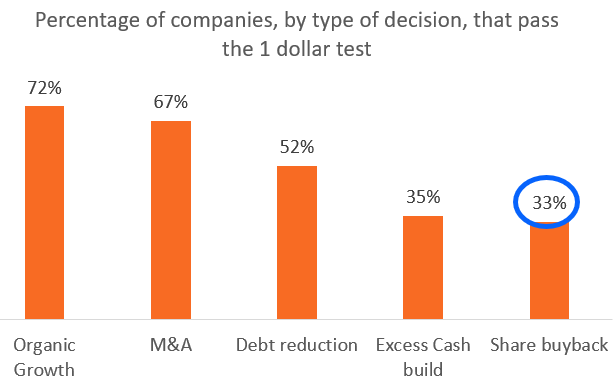

In 2021, Credit Suisse conducted an analysis of 1400 large and mid-cap companies in the United States and Europe. The goal was to check if the above framework corresponds to reality.

Here are the results of the one-dollar test for different allocation decisions:

Caption: Results from Credit Suisse, adapted by author

On average, one dollar invested in organic growth resulted in almost 2 dollars in returns. M&A returned about 1.4 dollars. Reinvestment in the business thus resulted in the highest return on investments which validates the above framework. If there is no need to strengthen the balance sheet or return cash to shareholders, reinvest to grow your business.

Surprisingly, on average, share buybacks led to value destruction. You routinely read that share buybacks are one of the holy grails toward finding a 100-bagger. More on that in a minute.

On the sample of 1400 companies, they also tracked how many companies achieved a positive return or how many passed the one-dollar test.

About 70% of the companies achieved a positive return while reinvesting their cash for growth. Half of the companies had a positive NPV by reducing debt. As mentioned above, only one-third of the companies actually created value by buying back their shares.

For this reason, let us take a closer look at share buybacks.

Share buybacks aren’t always gold

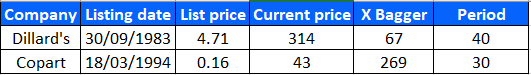

Let us take a look at 2 companies. The first one is Dillard’s. Dillard’s is a retail chain. They sell clothes, shoes, etc. This company has been around since 1938!

Since 2010, Dillard’s has become a cannibal. It is buying back its own shares at a steady pace. Dillard’s also returns a dividend to shareholders. Its current dividend yield is 0.32%. The graph also displays the P/E ratio. In 2011 and 2012, when the company’s shares were priced lower, they did a massive buyback. Afterward, regardless of price, they continued buying back shares. The goal here is not the asses their overall capital allocation strategy. Let’s compare their strategy to another company.

If you’re looking at the graph, and thinking about maybe getting on the train because the P/E ratio is the lowest it has been in the last 24 years, don’t forget to look at other criteria first.

Copart specializes in the resale and remarketing of used, wholesale, and salvage title vehicles for a variety of Sellers, including insurance companies, rental car companies, local municipalities, financial institutions, and charities.

Let’s take a look at how Copart bought back its shares:

Copart has the signs of a master capital allocator. Why?

It bought back shares twice when the share price was cheaper in the market. Since then, it has not bought back any shares. These are the signs that they evaluate different possibilities on a continuous basis instead of just buying back shares every year. They compare the intrinsic value of their own shares towards other capital allocation decisions they could make.

Both companies have a fantastic track record:

With Copart being the most successful one. If you think the Copart train still has a long way to go, and you want to jump on a moving train, last year was a great moment do to so.

There is no one specific rule when evaluating the capital allocation strategy of a company. If they bought back shares, look at how they’ve done it. What other capital allocation decisions did they make?

Let’s take a look at two other decisions, invest in organic growth and grow through M&A.

Invest in growth

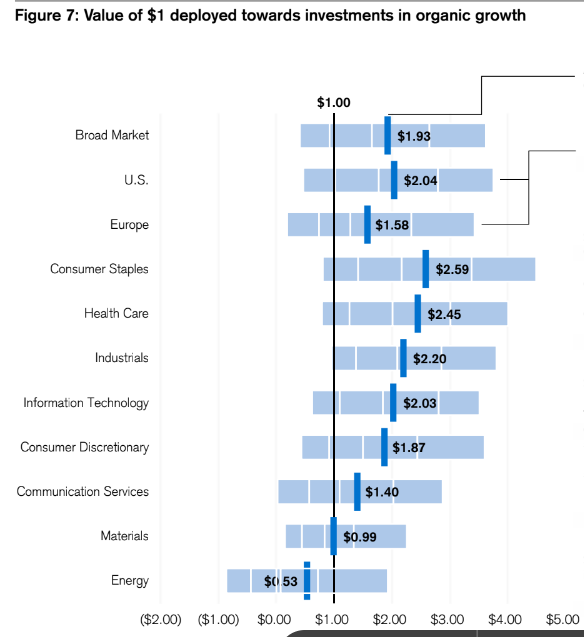

The goal is to build long-term value per share. This means buying new production capacity, creating a brand, doing R&D, etc…

Based on the Credit Suisse reports, companies can spend one dollar and create multiple of that dollar. 72% of companies pass the one-dollar test. But there are big differences across sectors. The number one sector that generated a multiple of 2.59 dollars was the consumer staples sector. The sector that lagged was the energy sector with 0.53 dollars. (the data from Credit Suisse ended in 2021, things have changed.)

Acquire other companies

Contrary to popular belief, on average, growth through acquisition is mostly value creative. One dollar created 1.39 dollars in value.

67% of all historical deals were value-additive for the acquirer. In other words, M&A can be a productive component for growth. This also means that on average, acquirers were investing in ‘cheap’ targets.

When a company is doing acquisitions, look at how its margins are evolving. If the company is a serial acquirer, the company should be strengthening itself by increasing profit margins and stable or increasing ROIC. Otherwise, you’re looking at those typical conglomerates of the past where 1 + 1 < 2.

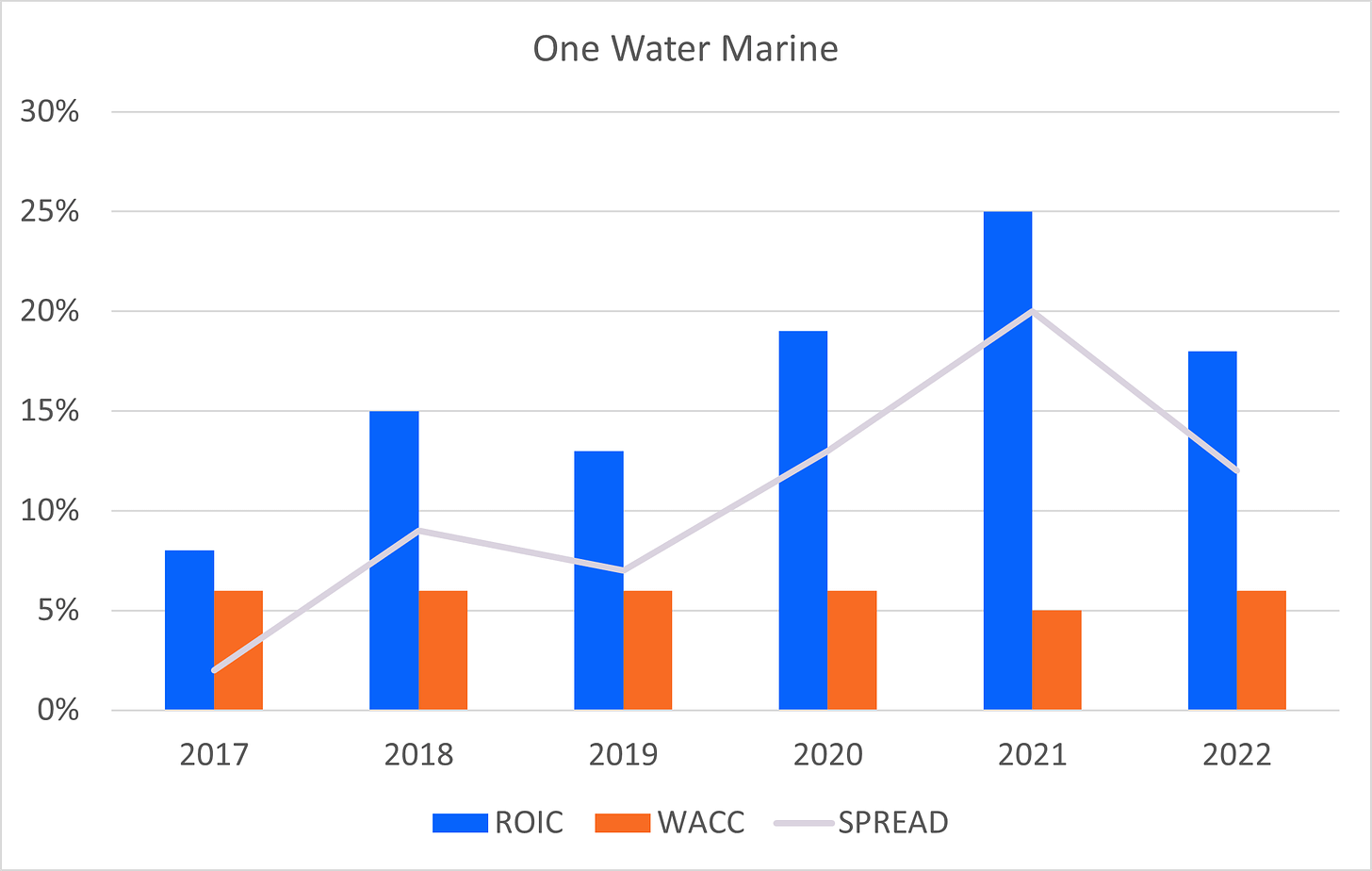

Here’s an example of a company called One Water Marine

One Water Marine is a boat dealer that is growing through acquisitions in a fragmented market. When looking at the spread, we can see it is increasing.

It’s gross margins and net margins have also steadily increased. It seems that their acquisitions are passing the one dollar test.

The business life cycle

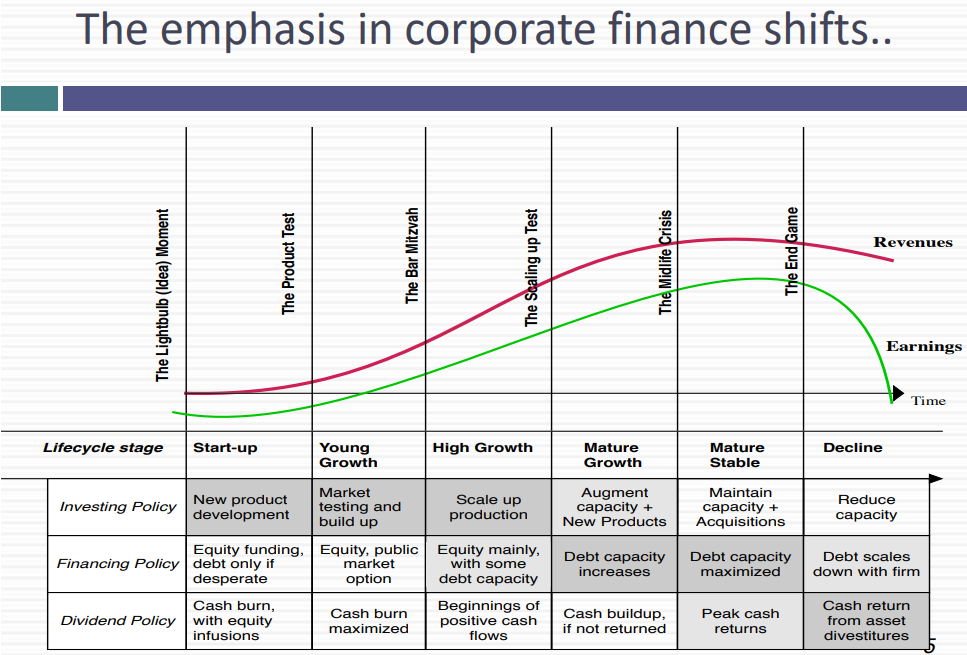

As we discussed before, every business goes through a business life cycle and a competitive life cycle. Capital allocation decisions are influenced by where in the life cycle a business is at the moment. It is useful to think about where the business is at this moment in time before evaluating its capital allocation strategy.

Here’s an image of the business life cycle by Professor Damodaran:

A young company usually is burning cash. They do not have excess capital so their focus is on getting financing to deploy that cash into growth and grow fast up until break even is met. They are usually funded by equity.

Once a business has scaled and is generating excess cash, now it can look at different investment opportunities. They could take on debt. Usually, reinvestment in growth is preferred, because if the business is still young, you want it to continue the compounding machine and not start to hand out dividends.

Once you have a mature business with strong cash flow generation, there are different possibilities. If a business is growing but doesn’t see any opportunities for reinvestment for growth, it could start distributing cash to its shareholders. A dividend policy might be established.

The best capital allocation decision will be: It depends, and we need to take into account the life cycle of the company.

An analysis of the competitive life cycle is needed if we want to look into the future. If the company has a history of creating value in the past, will competitive forces reduce this value creation in the future?

A capital allocation checklist

Now that we’ve developed a better idea of what good capital allocation really looks like, let’s go through some questions on how you could evaluate the allocation strategy of a company.

You can download the checklist in Excel here.

Where do you think the company is in its lifecycle?

You need this to be able to assess its past decisions.

Is the company creating value? Has it been earning an ROIC higher than its cost of capital?

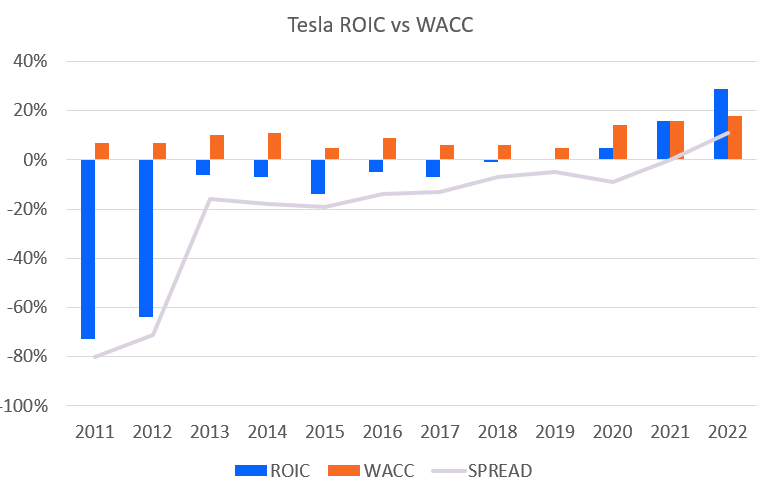

If it has been destroying value in the past, it doesn’t mean you cannot do the analysis. Tesla for example has been in the growth phase of its business cycle, and up until 2020 didn’t create value. It invested everything into growth.

What does the evolution of return on incremental invested capital (ROIIC) look like? The ROIIC value can vary widely. Look at these on a longer period basis (3 to 5 years).

How does the spread compare to its competitors? Is the entire industry earning a high return on capital? Are they significantly better than their competitors?

How was the company financed and how did they spend their cash in the past?

How did they use their capital in the past?

Investments in its operations to grow?

Acquisitions? -> If yes, have profit margins remained stable?

R&D?

Balance sheet?

Return to shareholders?

Do their actions make sense compared to their business life cycle?

Has there been a shift in capital allocation decisions?

Does management openly discuss capital allocation decisions?

If yes, what are their plans for the future?

Are they sitting on a cash pile, not knowing what to do with it?

Does management admit past capital allocation decisions and what they’ve learned from them?

Does management display knowing the difference between valuation and pricing? It it able to value its assets correctly?

Conclusion: Capital allocation and the 100-bagger checklist

If we look back at our capital allocation strategy in the 100-bagger checklist:

The previous paragraph showed how you could go about doing the analysis. Here’s how we could arrive at a conclusion for the 4 categories. There’s an example of a company in each category.

Yikes: The company has a history of destroying value. Look at the past ROIC versus their WACC. Calculate the value they destroyed. This value destruction continued after their growth phase in the business cycle. If the company has created value and is able to generate cash, it seems they have no clue what to do with it. (Cutera, Ticker : CUTR)

Meh: The company has created value in the past, but there is no real proof of a sound capital allocation strategy. It has been a hit-and-miss in the past, with overall positive returns, but management doesn’t show that they have learned from the past to do better in the future. They are sitting on a cash pile and cannot decide the way forward. They have made capital allocation decisions that are not in line with their business life cycle (generating dividends while the business is in full growth mode) (Company example: Inmode, Ticker: INMD)

Good: They have always created value in the market and their capital allocation strategy is clear, but it seems that they always do the same thing. You cannot find any signs of a changing capital allocation strategy based on the context and business life cycle. Proof of this can be the company is buying back shares without really looking at the intrinsic value. (Dillard’s, Ticker: DDS or Advance Auto Parts, Ticker: AAP)

Great: There is proof of an adaptive capital allocation strategy. Their decisions change with time and context. The management actually talks about capital allocation. There is a transparent strategy to maximize returns. Proof of this can be strategic buybacks when the intrinsic value of the stock is low compared to other possibilities in the market. (Copart, Ticker: CPRT)

What other companies are master capital allocators? What could we change to make the capital allocation checklist better?

Thank you for reading and as always,

…may the markets be with you!