Before diving deep into the DCF, a question for you:

If you’ve answered you never use a DCF, please leave a comment and let me know how you define the value of a company…

1️⃣ What is intrinsic value?

Warren Buffett has said it numerous times.

Intrinsic value is the current value of all future cash flows a business will produce until now and judgment day.

This has been known for over 2500 years, since the fables of Aesop, a Greek Fabulist.

A Nightingale, sitting aloft upon an oak, was seen by a Hawk, who made a swoop down, and seized him. The Nightingale earnestly besought the Hawk to let him go, saying that he was not big enough to satisfy the hunger of a Hawk, who ought to pursue the larger birds. The Hawk said: “I should indeed have lost my senses if I should let go food ready to my hand, for the sake of pursuing birds which are not yet even within sight.”

—Aesop’s Fables: A New Revised Version from Original Sources (translator not identified), 1884

In other words, a bird in the hand is worth 2 in the bush. The lesson behind it was:

Be happy with what you already have.

Of course, when linking it to the craft of investing it becomes something else.

Indeed, a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush—unless, perhaps, the probability of catching the birds in the bush is very high.

Here’s a great video about Warren explaining intrinsic value.

But details are important, he says:

How sure are you that there are 2 in the bush?

How far away is the bush?

A discounted cash flow model is a way to explicitly calculate the above, and see if the value is larger or smaller than the current price of a business.

And yet, a lot of investors don’t like the DCFs (I wasn’t a fan either).

Rules of thumb (P/E ratio) or relative valuation (comparing businesses) are a lot easier and feel more reliable.

In addition, the master himself doesn’t use DCF’s:

"Warren talks about these discounted cash flows. I've never seen him do one." "It's true," replied Buffett. "If (the value of a company) doesn't just scream out at you, it's too close."

Charlie Munger at the 1996 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting

Why he doesn’t he explained in the past:

“The question is, how many birds are in the bush? What is the discount rate? How confident are you that you'll get [the bird]? Et cetera. That's what we do. If you need to use a computer or calculator to figure it out, you shouldn't [buy the investment]. Those types of [situations] fall into the "too-hard" bucket. It should be obvious. It should shout at you, without all the spreadsheets. We see something better.”

Again details are important. He may not use Excel or a spreadsheet to do his calculations, but that doesn’t mean the definition of intrinsic value is wrong.

In other words, Warren agrees with the definition, he’s just saying that you shouldn’t need an Excel sheet to calculate it. The value of the business should be screaming at you.

I would argue that the Excel sheet itself is of minor importance. The set of questions we ask to go about defining intrinsic value is what is.

In the above discussion, there is 1 question that is often neglected:

How far away is the bush?

2️⃣ The competitive life-cycle

We already went through a part of this when we discussed how to measure a MOAT.

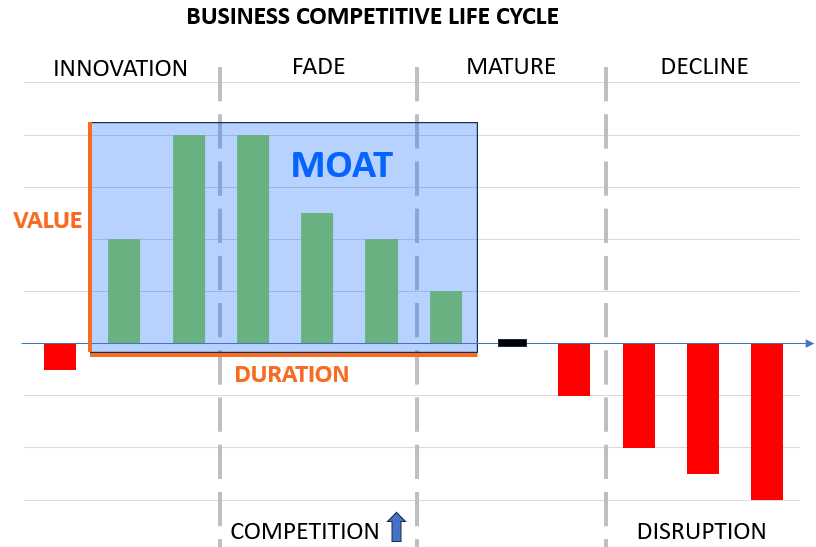

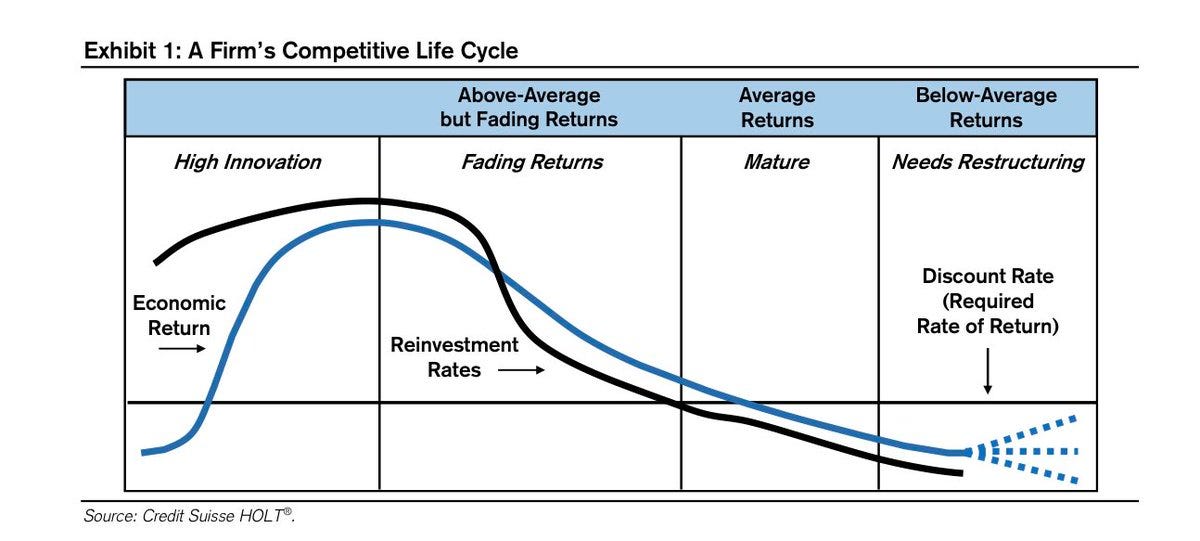

Every business goes through a life cycle. If successful, it will grow fast during startup, get into high growth mode, and start to generate earnings. Then growth stabilizes, and the business matures, until eventually decline sets in, and the business will fade out.

The competitive life cycle has 4 phases:

Innovation phase: During a period of high innovation, the return on invested capital increases rapidly. Once it surpasses the discount rate, value is created. These are young companies before they go public

Fade phase: Marauders attack the castle. Returns start to fade. Value is still being created, but margins are taken away.

Mature phase: Companies now reach a balance in the market. The castle’s MOAT has narrowed. On average, the companies earn the cost of capital.

Phase of decline: Competition and technological innovation by new entrants drive returns below the cost of capital. A restructuring of the company might be needed. Value is destroyed in the market.

Here’s the same graph where the above picture is based on from Mauboussin’s paper on how to measure the MOAT.

At some point in time, reversion to the mean will occur. When, depends on the size of the MOAT. The wider the MOAT, the longer this reversion will be prevented.

It is the when that is of interest…

3️⃣ The competitive advantage period

The simplest DCF calculation has 3 parameters:

The base Free Cash Flow in year 1

The growth rate

The discount rate

And as discussed in more detail before, the value of a company can be divided into 2 parts:

A steady state value component

A future growth component

The future growth component is proportional to the competitive advantage period.

At the end of this period, we find the bush, with the birds.

This means, if defining intrinsic value, there should only be 2 periods:

The first period where the business earns excess returns

The second steady period of perpetuity

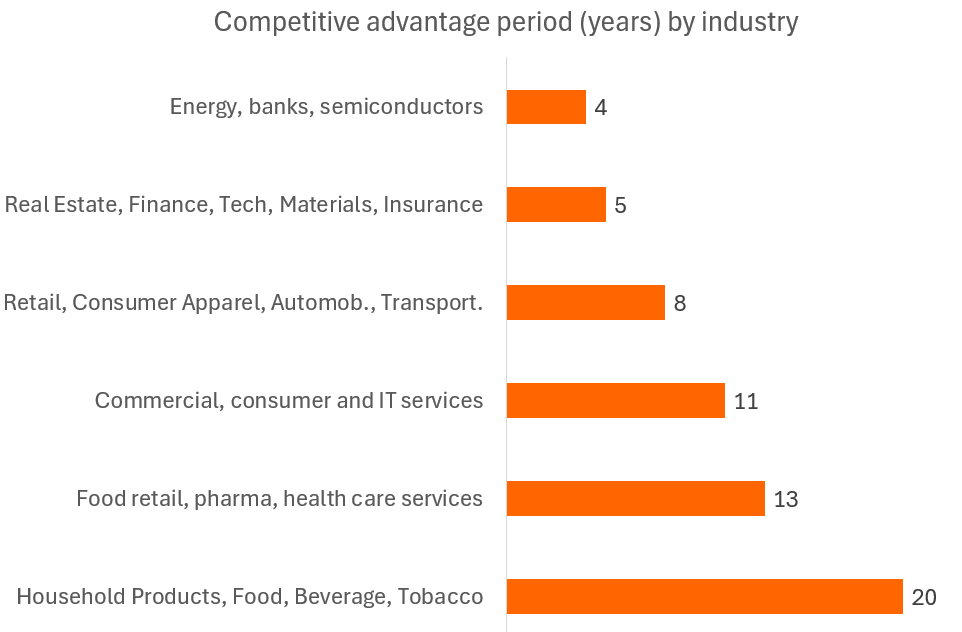

The duration of the first period depends on the MOAT of the business. It could be 4 years, it could be 20 years. Credit Suisse ran the numbers by industry.

Here is a summary:

Sector-wise, the CAP is inversely proportional to the rate of change in the sector. This makes intuitive sense, technological advancement in semiconductors has been high over the past decades.

So in other words, we should add a fourth parameter to the simplest DCF model you can develop: The duration.

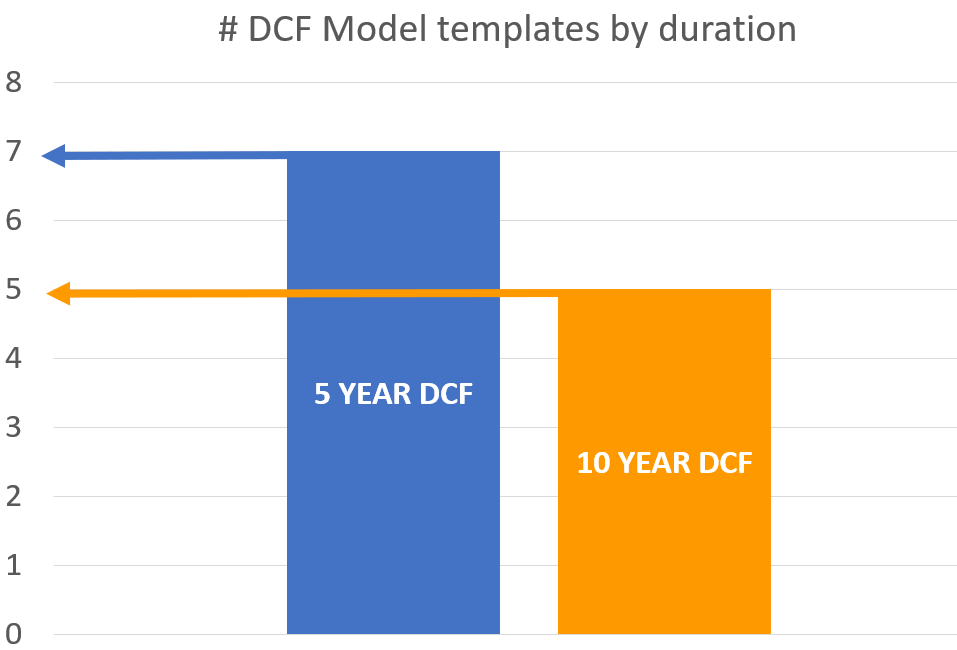

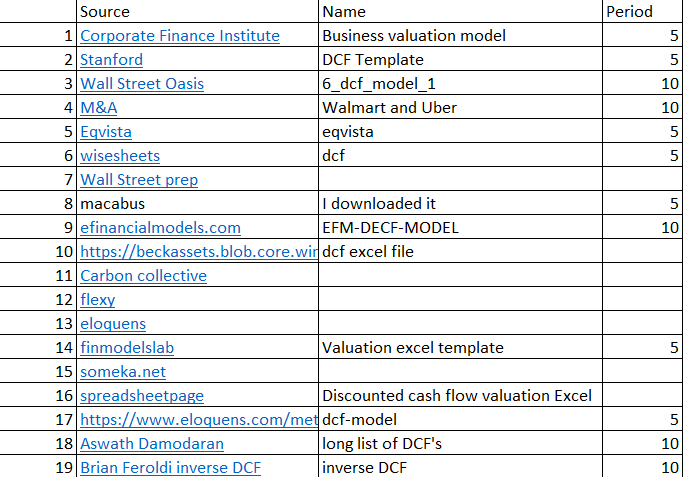

And yet when I used Google to download a couple dozen DCF templates, here’s what I found:

In fact, I only found a single Excel where you could choose the DCF length.

If you would like to check out the list of templates, just click the image below:

If the duration of the DCF is set at 5 years, often, a lot of the intrinsic value will be captured in terminal value.

So after numerous articles on the subject, including an article about Michael Mauboussin in 1997: Competitive Advantage Period - The Neglected Value Driver it seems that not a lot has changed over the last almost 3 decades.

It almost seems that the length of all these DCF models is based on the number of fingers we have on our hands.

There are however some reasons to justify this:

Going beyond 10 years is too uncertain

Going so far out, change cannot be forecasted

Discounting a cash flow 20 years in the future will make it very small, it doesn’t matter

However, for certain businesses, in industries where less change is prevalent, it might be useful to go beyond the standard length.

4️⃣A quick example

Let’s consider a business with a big MOAT where we can confidently assume that it will continue to generate excess returns for the next 20 years.

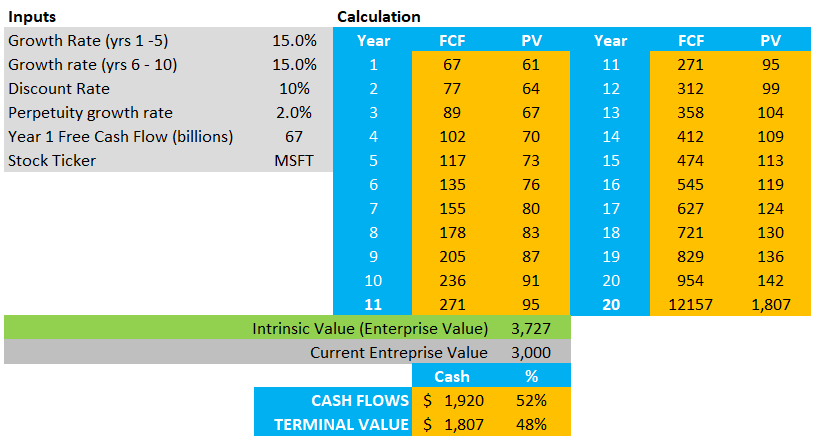

We’ve chosen Microsoft because it will probably dominate a big part of its business for the next 20 years meaning, we consider it has a CAP of 20 years. (although it sits in a sector where the average CAP is smaller).

Yahoo Finance tells us that the estimated 5-year growth for Microsoft is estimated to be 15%. Let’s plug it into the most basic 10-Y DCF you can find.

Intrinsic value = 2 trillion compared to a current enterprise value of 3 trillion.

60% of intrinsic value comes from the terminal value and 40% from the first 10 years of cash flows.

This model is far from perfect as we postulate 15% growth during the next 10 years and then suddenly growth drops to 2% into perpetuity. The goal here is not to find the perfect model, the goal is to see what happens if we add 10 years and see if it makes sense. Here’s the same model over a 20-year period.

An additional 10 years doubles the intrinsic value and makes it so that cash flows and terminal value are more in equilibrium.

But that’s absurd. Microsoft will not continue to grow at 15% CAGR for 20 years. I have no idea. The only thing we know is that over the last 20 years, it grew free cash flow at a 10% CAGR.

If you had calculated the intrinsic value of Microsoft 20 years ago, would it have been better to project over 20 years, or take the standard 5 or 10 years into account?

I do not care about the sensitivity of a DCF model or the fact that going beyond 5 years is complete nonsense.

I care about asking the right questions to value a business, in an explicit way. (instead of being hidden behind rules of thumb).

If you want the Excel with the above simple DCF model, you can download it below.

5️⃣The reverse DCF

One of my favorite books is Expectations Investing by Michael Mauboussin.

Invert, always invert

Charlie Munger

Instead of trying to define the intrinsic value of a company, what is the market saying about the implied growth rate or competitive advantage period of a company?

Here’s a simple example of how he does this.

If the value of an asset is defined by:

Cash flows

Risk (or discount rate)

Competitive advantage period

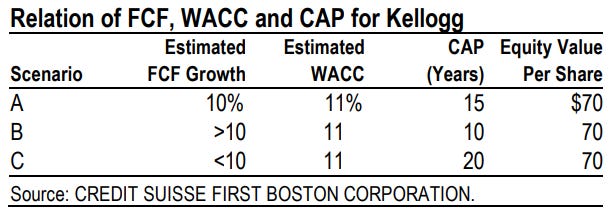

Then for a given price in the market, and after having chosen the discount rate, you can define a combination of FCF growth rate and CAP.

In his 1997 paper, he does this for Kellogg:

This is where strategy meets finance. Explicitly reflecting on the CAP in a reverse DCF allows you to link the duration of the MOAT of the company to its valuation.

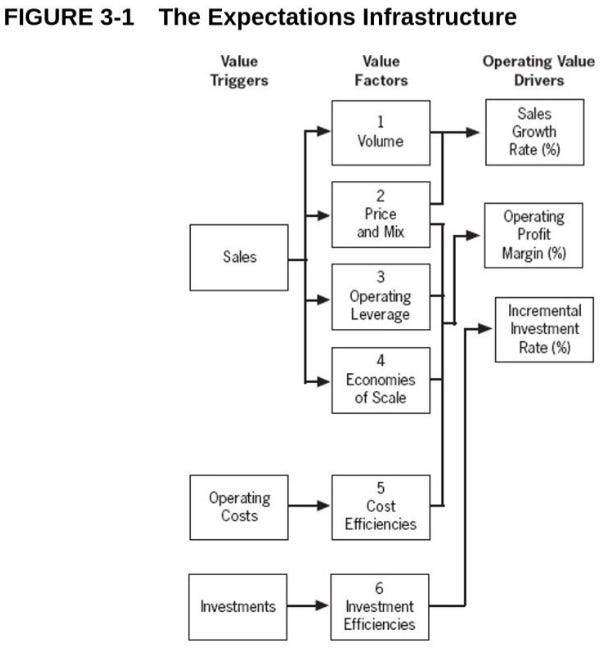

The FCF can then be broken down into its drivers, sales, margins, capital needs, and taxes, to understand what the market is implying.

But we’ll unpack that in the future in a more detailed article.

If you would like a simple reverse DCF template,

has a good one because it starts by looking at where the company is in its life cycle.6️⃣Summary

I think a DCF, reverse or not, should be a part of an investor toolkit

The reasoning behind it is more important than the actual result

A company’s MOAT can be linked to the DCF by the competitive advantage period

The CAP on average is different by sector, but as a value driver, it is still neglected

A reverse DCF is the best tool to understand what the market is thinking

7️⃣Further reading

Here you can read how

uses an inverse DCFA reverse DCF applied by

to PalantirAnd the implied growth of Elastic N.V. by

I define the value as the market price. Intrinsic value has never worked for me. Alibaba / my best example. US stocks seem to trade way too expensive. I was told stocks move towards this “intrinsic value” but it just has not worked on what I have tried. The only thing I can rely on is technical analysis at this point in my studies. Not giving up on fundamentals as I have only been trading about 6 years. Wild time to learn the markets. The internet does help though and feel fortunate that I have it while many of the researchers I look up to didn’t have that access.

Great article Kevin. I personally find the journey of calculating a DCF more useful than the destination or answer. Mapping out how revenue, margins and cash flow will evolve over time requires a deep understanding of the underlying business and drivers. I find this to be the most valuable part of the exercise.