A strategy to increase your holding periods and get better returns: The Reactor Portfolio

Introduction

During the daytime, I’m a nuclear engineer. Over the past years, I’ve started to apply more and more nuclear engineering principles to my investment approach which led to great results. Working in a nuclear power plant is all about risk management. The very first question we ask every time is:

What can go wrong? What is the worst-case scenario?

These are some of the most important questions to ask before starting an investment.

Focus on the downside risk, and the upside will take care of itself.

-Mark Sellers, former Hedge Fund manager

Lately, I’ve changed the way I approach my portfolio design. I now manage a reactor portfolio. What does this mean?

Let me first explain how a nuclear reactor works.

A nuclear reactor

In its simplest form, here’s how a nuclear reactor works.

Neutrons react with Uranium. Uranium is split and generates energy and new fast neutrons.

The energy is used as heat to create steam, which drives a turbine where a generator produces electricity.

The new neutrons are there to generate more reactions and keep the system going

The reactor core holds the fuel assemblies with enriched uranium.

Neutrons are generated at amazing speeds. The core on itself is insufficient to sustain the needed reactions to produce heat and eventually electricity.

Why?

Because when only fast neutrons are created, insufficient reactions occur (the probability of reactions increases when neutrons are less energetic). We need to slow these neutrons down.

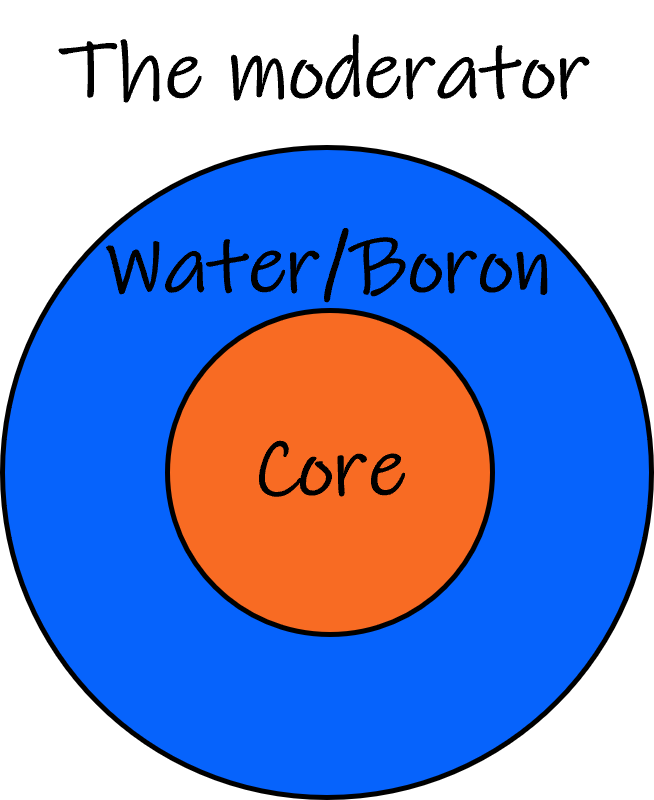

In comes the moderator.

This is usually borated water. The fast neutrons will collide with the water and slow down. More reactions will occur. If we find a balance between the reactor core and the moderator, we can achieve a sustainable system.

There’s one final problem. Neutrons escape. Some are not slowed down or some are but will continue to travel and leave the reactor and moderator.

What happens when a neutron meets another element?

Transmutation (lead turns into gold!) Sadly this is not the case, but Cobalt-59 turns into Cobalt-60 and starts decaying and putting out gamma radiation, which is not good. It’s also not a good idea for a human to be exposed to neutrons or gamma radiation (sadly you won’t get strong like The Hulk). Radiation can be damaging.

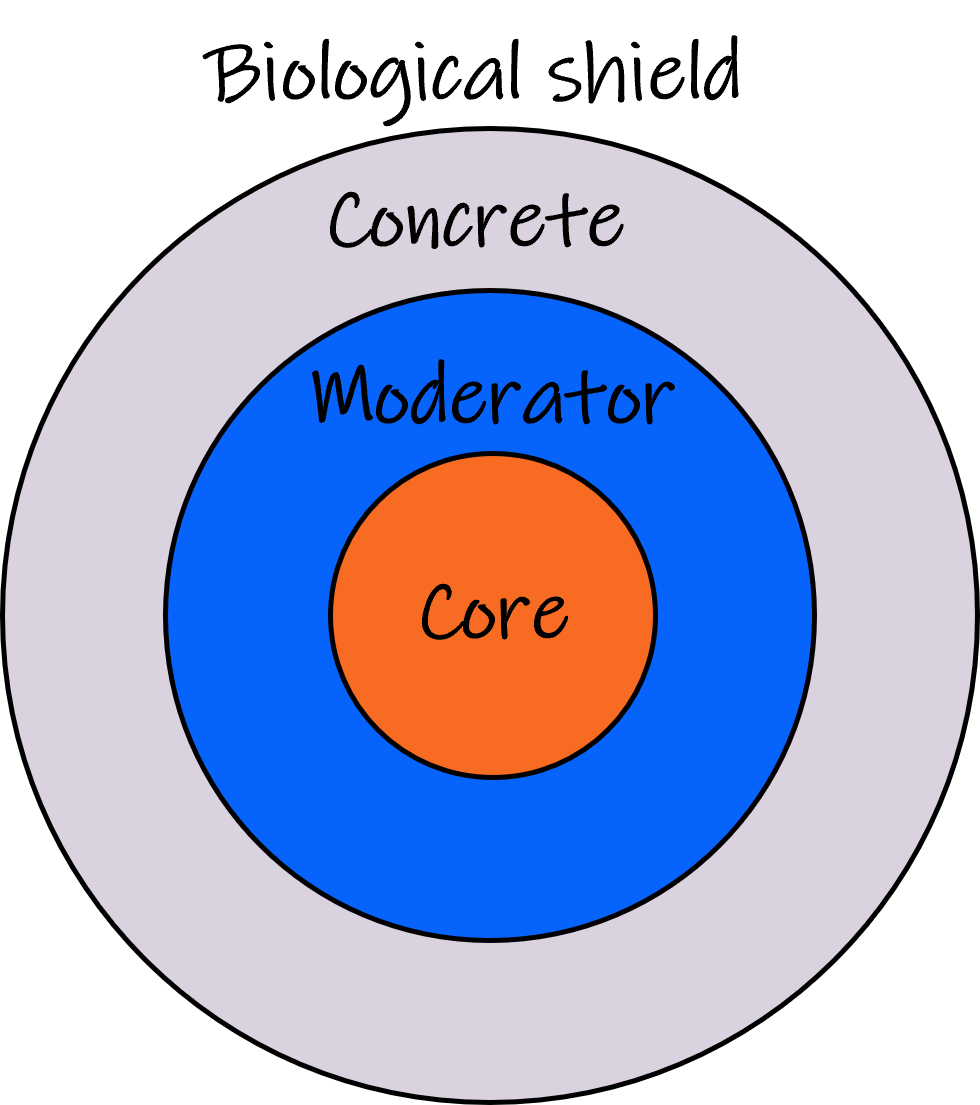

In comes the biological shield:

This is the final piece to the puzzle. A thick concrete wall with steel lining will absorb all neutrons that would want to escape from the reactor. Neutrons collide, slow down even more, and are eventually captured. Our reactor now works.

So what does this have to do with investing? Let’s get to the source of the issue.

A classic portfolio

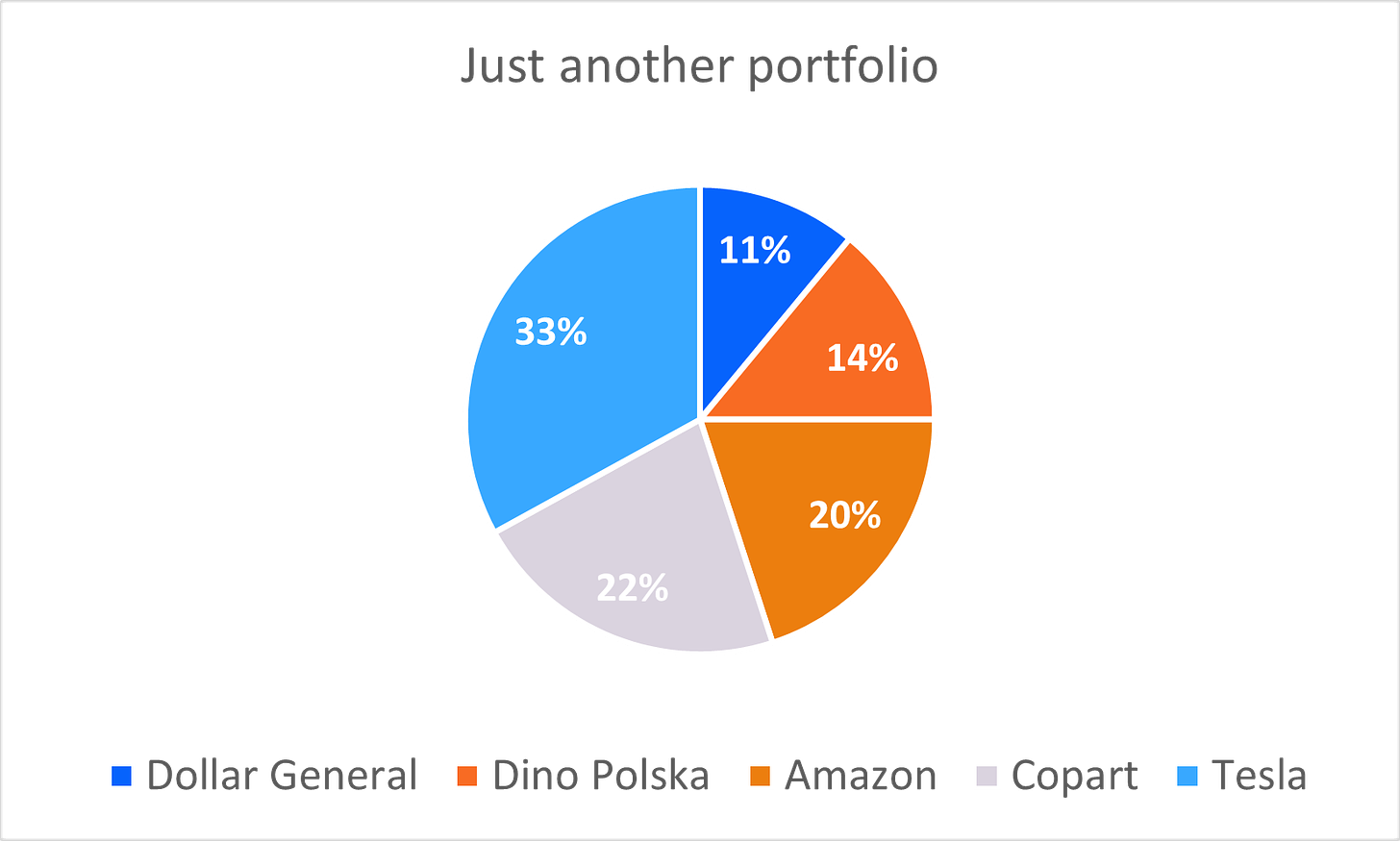

A typical view of a portfolio looks like this:

This is not my portfolio, it’s just an example. Although I wish I had built it a decade ago.

Your holdings are displayed by a percentage or dollar amount. Maybe you run a concentrated portfolio like Charlie Munger of only 3 or 4 companies, or you have a lot more positions in your portfolio like a lot of funds have.

The problem with this it’s one-dimensional (only one parameter is used). Besides displaying your largest positions or how diversified you are, it does not give a lot of information about your investing strategy. You can use it as a risk management tool if your holdings get too big (which most fund managers have to do, trim their winners). Or better, you can draw up the portfolio based on cost (how much money you’ve put in relative to total cost) and use that as a risk management approach.

But we could do more. There are 3 reasons to make the portfolio two-dimensional.

Temperament

People say I’m unemotional. An analyst. Someone who only cares about the data and the facts. This is true to some extent.

But when I buy a stock and it drops 40% in the next week (yes, it happened to me), I do feel my emotions, pulling at me, spraying doubt into my mind. It feels like getting hit in your stomach.

Was this a good idea? Should I not sell a part of my position?

Suddenly, you take notice of all the bad things related to your investment.

The opposite is also true. You value a company and have a good price in mind. The stock is trading just above that price. Suddenly it jumps by 20% in the market.

Damn. I really wanted to buy that one. Should I modify my limit order? Just a little bit?

Watching the price of a stock you’ve invested time (and/or money) in generates an emotional response. That’s one of the reasons why I never buy or sell when the market is open. I put in a limit order when the market is closed, and I cannot touch the level of the limit (I learned this from an interview I saw with Guy Spier).

Trading versus investing

I always considered myself an investor. But I was wrong in the past. If I bought a stock and sold it for a nice 30% profit in the same year, I was happy.

But does it move the needle?

If I could do it over and over again sure, but the reality was, I wasn’t able to do it over and over again.

After reading 100-baggers by Christoper Mayer, I wanted to change my investing strategy. Use the time effect, the compounding power of the market. Although my intentions were good, I was still distracted by all the ideas and opportunities that were thrown at me.

Starting to write on X did not help.

“The trick in investing is just to sit there and watch pitch after pitch go by and wait for the one right in your sweet spot.

-Warren Buffet

Easier said than done. Simple in theory, difficult in practice.

Exit strategy

When you buy a private company, an exit strategy is very important. Without an exit strategy, how will you ever see a return on your investment? An exit for a private company could be:

Being acquired by a Private Equity firm or other company

An Initial Public Offering (IPO)

Maybe you can find someone to sell your shares to (several platforms exist nowadays, but please be careful with these)

In any case, it is by definition illiquid. This can be a good thing. Illiquidity can be your friend. An additional benefit: you cannot see the price of the company changing all the time. Without having a firm grasp of the exit strategy, you should never buy a private company.

We should apply this to the public markets. Although public markets can be very liquid, we should never buy a stock without an exit strategy. Here’s an example of the exit strategy I’m currently refining for a holding I have, Inmode (see deep dive here).

Inmode Selling Rules:

If top-line revenue starts declining more than expected quarter to quarter over 2 years. Why is this happening?

If management, over the next 5-year period max does nothing with the cash.

If gross margin starts to drop in the coming 5 years due to increased competition. (where Inmode is having to reduce the prices of their products)

I’ll go deeper into this in the future, but the exit strategy or selling rules have nothing to do with the price in the market. They are only related to business fundamentals, and I try to specifically mention a time frame. Notice I’m talking in years and not quarters because the underlying fundamentals won’t change that fast (although Inmode stated declining revenues in the latest quarterly update).

The Reactor Portfolio

We’ve discussed several problems I had as an investor. How can we find a strategy that:

Lets me focus more on the long-term

Allows me to scratch that itch to trade sometimes

Forces me to always have an exit strategy

In comes the reactor portfolio.

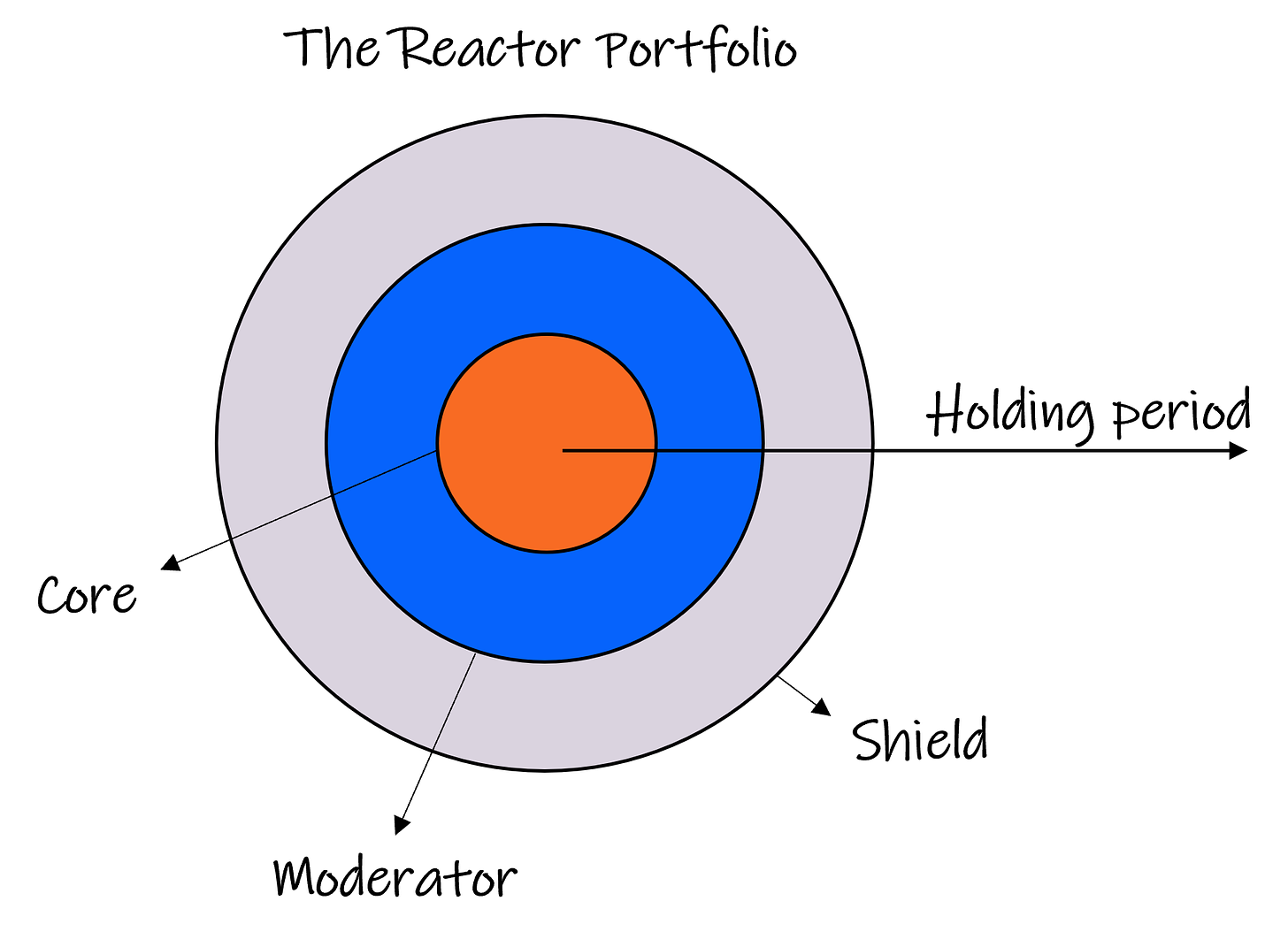

The reactor portfolio is designed as the abovementioned nuclear reactor. Let’s build it up.

You have some holdings in your core. These are the companies you’ve bought and want to hold for the short to medium term. This is where you’re scratching that ‘trading’ itch.

It’s ok son. You’re allowed to.

Holding periods are shorter. These holdings can come with a lot of volatility, but as we know, volatility does not equal risk.

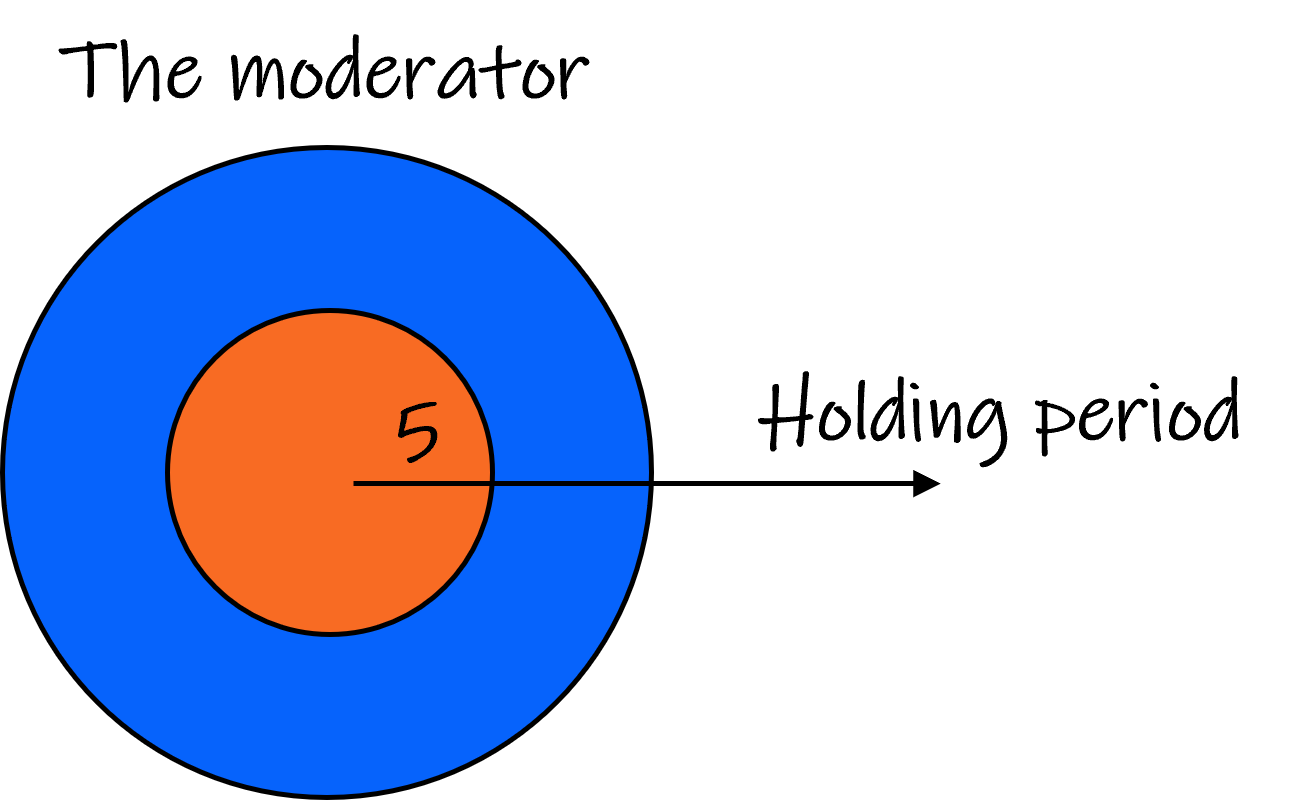

I’ve put 5 years max in the reactor core. The maximum holding period is for you to choose. Maybe it’s one, two years, or even 10. That’s for you to decide. Now let’s look at the moderator.

The moderators are your longer-term holdings. They moderate your entire portfolio. You do not trade these often. But on the other hand, based on your analysis, you do not see yourself holding these longer or forever. Notice that we didn’t specify a holding period. That’s because the holding period will be shorter than the holdings in your shield.

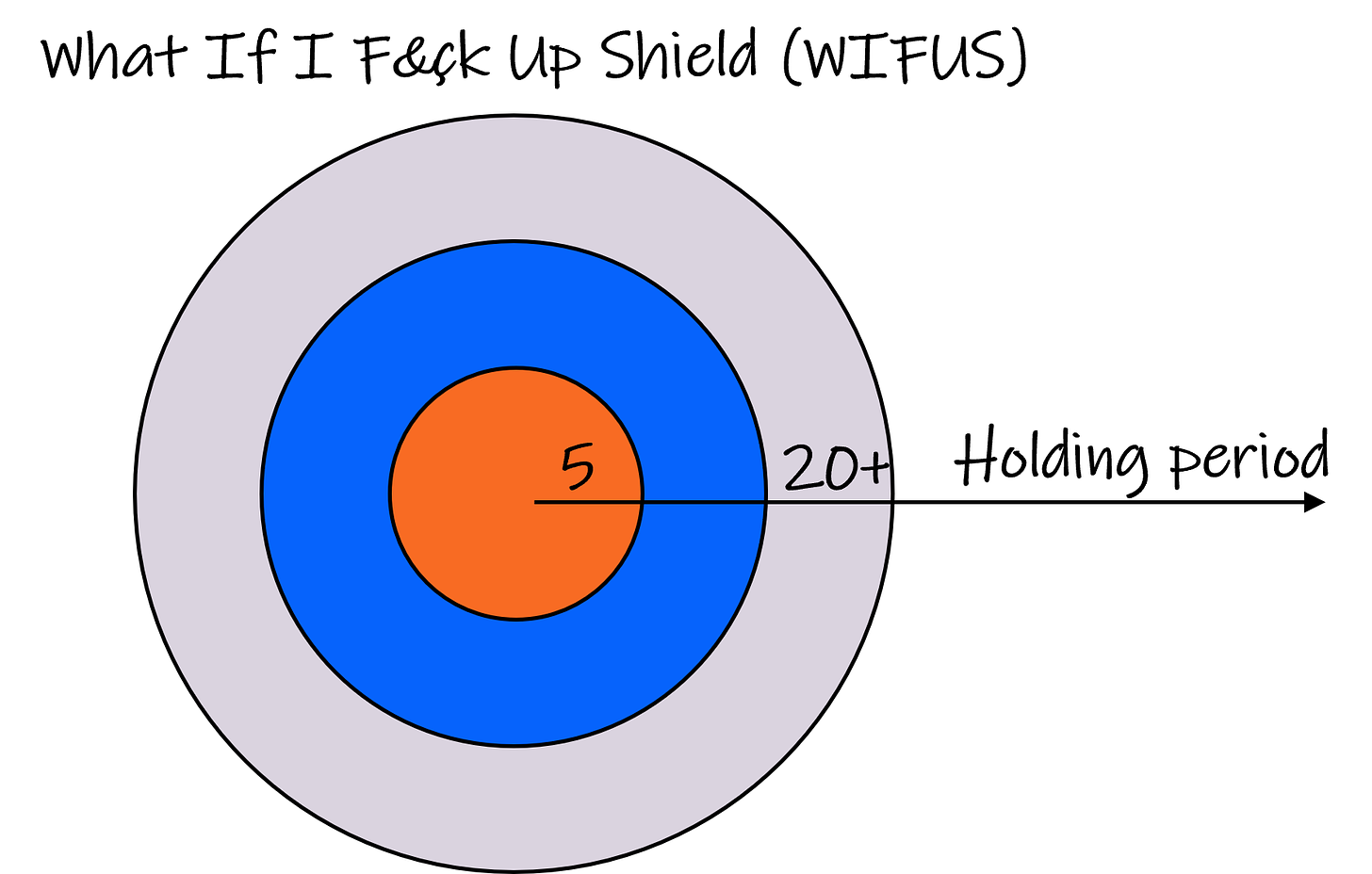

Finally, we need the biological shield. I also call this my What If I F&çk Up Shield (WIFUS). It tells me to stay humble. These are holdings you would never sell or keep for a very long time. These are the rocks or solid tree trunks inside your portfolio. I’ve chosen at least 2 decades as my shield.

Because we’ve added a second dimension to the portfolio, the estimated holding period, you are forced to think about a possible exit one day. The final reactor portfolio looks like this:

How big each layer becomes depends on you as an investor and on your strategy. I mainly invest in private and public companies. But maybe for some, the reactor will contain crypto, and the shield will contain index funds. An investing strategy is a very personal thing.

My investment journey

Let’s use the concept of the reactor portfolio to show you how my investing strategy has evolved over the past decade.

Humble beginnings

I started by buying smaller individual stocks, sometimes commodity-related. My average holding period did not exceed one year. There was no moderator or shield. Later I dabbled in crypto. You can imagine a very volatile core, with lots of buying and selling. In the end, I did OK, but it was more related to luck than actual knowledge, skill, and temperament.

Because I wasn’t satisfied and based on what I had learned, I did the following:

I made the volatile part of my portfolio smaller and started to buy larger-cap companies like utilities. The problem was, that my holding period was still pretty short. Honestly, I did not have an exit strategy at that time. I’ve added the holding period as an example, but I didn’t think about it.

Light at the end of the tunnel

Then I saw the light, index investing or passive investing. Here’s what happened:

The passive investing layer became my shield. This for me is a great strategy for most people who do not have the time to learn about investing. A big part of their portfolio is in an index and a small part is a couple of companies to play with.

I only had one problem. I love business analysis, accounting, etc. and I kept reading and learning. The core part of my portfolio did better than the shield. So I started increasing the core and decreasing the shield. This may prove to be a bad idea in the long term, but for the moment, I’m happy with my strategy.

So here’s my strategy now with some examples, to illustrate the point:

My reactor core has a holding period of up to 5 years, not longer. These are smaller, quality companies that for some reason have depressed pricing in the market where I believe they will recover. I’m explicitly looking for asymmetric bets. This scratches my trading itch and allows me to leave my other holdings alone.

For the moderator, these are holdings that I would hold longer than 5 years but not forever. These are quality companies, but they may not have a wide MOAT. So I do not see them compounding forever. Adyen is one example where it is an exceptional company, but its MOAT might be eaten away by competition in the coming years. I’m writing a deep dive on it, so stay tuned.

For the shield, these are true long-term compounders I hope to never sell. Because I do consider that I invest to eventually use some of the proceeds in my life, I’ve put a holding period for 20+ years in it. It is up to you to choose it based on your context.

Within the moderator and shield, I try to find opportunities that provide outsized returns by holding them longer than most investors. These are not necessarily asymmetric bets because these companies are never cheap.

Remember the average holding period in the market:

Is it because of high-frequency algorithmic trading in the market? Maybe the gradual reduction in fees on trading had a big influence. Company life spans are shortening because of a higher innovation rate. In any case, your edge as an investor can be to hold a stock for a longer time.

Displaying your holdings as a reactor portfolio gives a lot more information about what you think about your holdings and has the added benefit that you force yourself to explicitly mention the holding period you have in mind.

A holding period is of course not set in stone. Based on your company and investment analysis, you define the holding period, and with your exit strategy, you will track the company regularly. If the company breaks your thesis, you may sell sooner, if the company goes beyond your thesis, you may hold the company for longer, and maybe move a company from the core to the moderator.

Example: If Inmode somehow succeeds in exploring new markets and sustaining a good revenue growth rate for the coming years, it may prove interesting to hold the company a little longer.

Notice that for clarity and explanation purposes, I did not change the surface of the circles to match the position sizes in the portfolio. I’m building a tool to make it easier to generate the above presentation. More on that in my annual review at the end of the year.

My goal is to gradually create more gray or blue, and increase the part of the shield and the moderator.

Conclusion

Instead of focusing on potential performance and returns my goal is to focus more and more on the holding period. Using the reactor portfolio helps me do this.

Michael Mauboussin wrote about it in one of his many articles: The Competitive Advantage Period, the Neglected Driver.

Value is the product of excessive returns over a certain duration. We don’t focus enough on thinking about the duration part of this equation.

Thank you for reading and as always,

May the markets be with you!