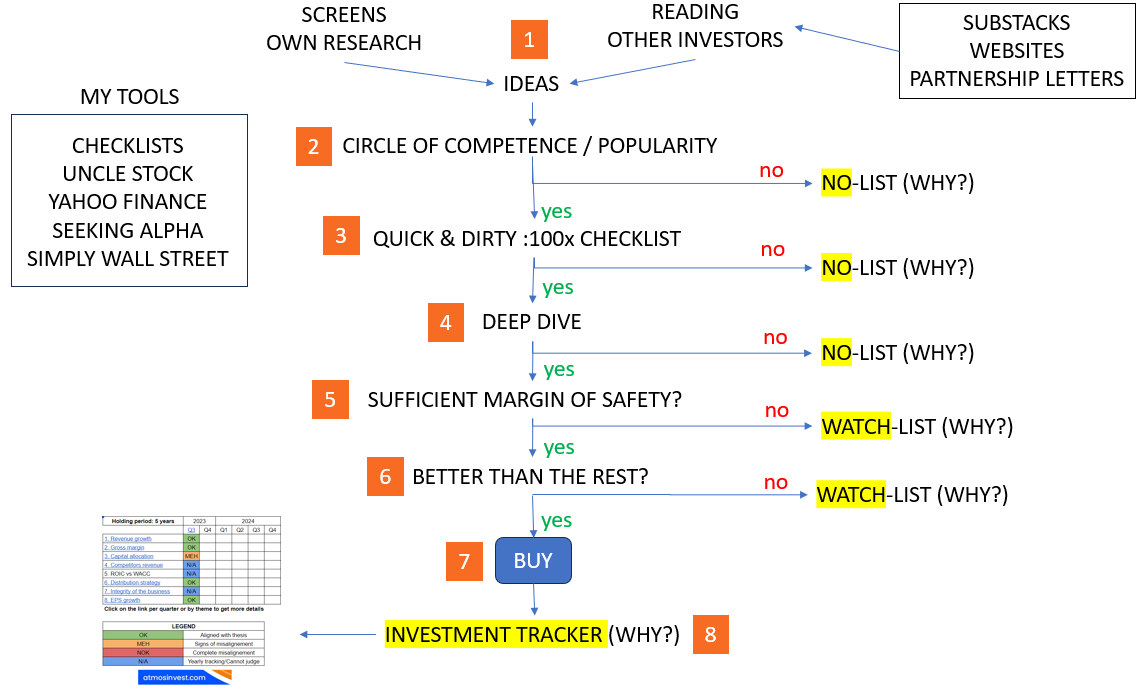

The 8-step AtmosInvest Investment process

Introduction

Although several articles that I’ve written in the past mention what style of investment I use, using the latest annual review I wanted to write down in detail what my investment process looks like, for myself and maybe for the benefit of you.

One of my favorite podcasts is the Jro Show because John goes into the nitty gritty details of the process used by professional money managers.

So, we’ll dig into what kind of companies I look for, how I tackle risk management and portfolio optimization, and what my current checklists for my investment decisions look like.

To start simple, here’s a schematic of what my entire process looks like.

Well, maybe not that simple. Let’s go through the process in steps, but first, a short discussion about going private.

Private companies

I invest in private and public companies. I do this because I consider there shouldn’t be a difference between the approach towards these investments. It’s a reminder to me to treat every single one as a company, and not as a stock (which is easier for a private company). Although I could discuss my private investments here on the substack, the reason I do not is that they are mostly uninvestable for the reader. In addition, I prefer to write about public investments because the lessons are similar and it is more actionable for you if, after your due diligence, you would consider investing.

My reasoning for investing in private companies is also related to the amount of alpha an investment can create. In the US, where there’s a fully developed venture capital market, a lot of alpha is generated by venture capitalists. Once companies go public, they are usually pretty big in market cap. Less alpha is generated afterwards although the magnificent 7 prove otherwise. In Europe, this early-stage capital market is less developed, and private companies sometimes provide opportunities to get into a capital raise without the need of having to go through a venture fund. These remain high-risk, high-reward bets.

The overall strategy

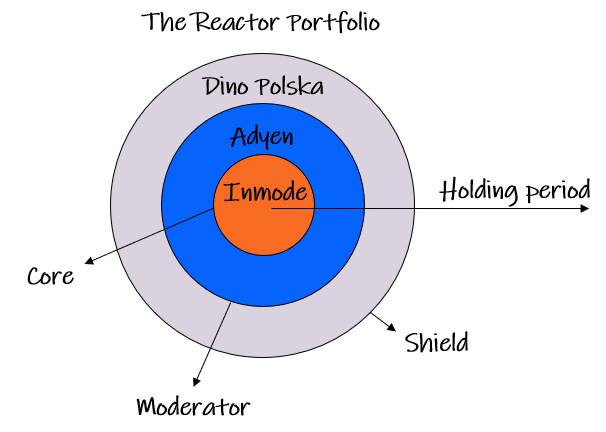

I employ essentially a 3-fold strategy in my investing approach as I discussed when describing my reactor portfolio.

The core of the portfolio is focused on:

Smaller companies

Higher risk

More volatility in the stock price

A company like Tinybuild or Inmode resides here. Holding periods are usually shorter. The risk is higher, and the position size in the portfolio is usually smaller (usually, I’m referencing the mistake I made earlier with Tinybuild) I’ll get back to this core part of the portfolio when discussing how I’m changing this core based on what I have learned from Paul Andreola’s investment strategy.

At the outer side of the reactor portfolio, we have quality compounders. These are high-quality companies (high ROIC) that have a proven track record of compounding returns in the past, and which I believe still have an important runway ahead of them to keep compounding in the future.

These are not cheap in the market. As usual, we need to do the work beforehand and then wait until the price drops to a level we think is fair. An example of companies I own in this part is Dino Polska. These are companies that I would consider putting in a “coffee can” portfolio to never touch again. Holding periods can be in the decades.

Then we have companies that reside between these 2 extremes. Companies that are bigger, but are growing rapidly. They are not clear compounders but do have a large runway ahead of them. A company like Adyen for me fits this bill. Holding periods are longer, but I would never put Adyen in a coffee can. We need to keep track of the company and see if it can continue to deliver.

Once a company is selected and invested in, it goes into one of the 3 parts of the portfolio. The reason I display my portfolio this way is to make me hold on to the companies as long as possible.

Whatever the company, it always goes through different checklists like the 100-bagger checklist or the MOAT or capital allocation checklist.

The 100-bagger checklist is different in that the results are not a NO or YES. The result is to get a sense of the quality of the company compared to its pricing. You could say that if everything is GREEN on the checklist, then you have a high-quality company for a very low price. I haven’t stumbled upon this in all my years of investing. The markets usually catch on pretty quickly.

The MOAT and capital allocation checklist exist to help me structure my write-ups. You’ll always find a discussion on what the possible MOAT and capital allocation strategy for the company looks like.

To end this strategy, certain factors will always be present in my holdings, may they be microcaps or midcaps, compounders or not.

Insider ownership: I will never buy a company that has a low percentage of insider ownership. Preferably, the insider ownership is divided among several members of the board and management team (as opposed to 1 single person having 60%) of the company. The goal is to have, all incentives aligned as much as possible.

Strong balance sheet: It has no debt or manageable debt. I will never invest in a company with high levels of debt. Based on my 2023 review, I might be leaning toward strong balance sheets instead of fortress balance sheets (only cash). Debt on itself is not necessarily bad if you know how to manage it and if you can earn at a rate that is higher than that at which you borrow.

The 8-step process

The investing process itself is devised as a funnel. Lots of ideas come in, only a few decisions are made at the end.

Step 1: Idea generation

In step 1, an investment idea for a company is generated. This can be through reading other articles, books, or substacks, or discussions I have on X regarding certain companies. Ideas come from all over the place.

To give you an example, one of the best letters out there is from Sohra Peak Capital.

Step 2: My circle of competence

I’ve seen a lot of great investment ideas on other substacks like companies in the oil and gas space or banks. (go look at some great articles by

or a deep dive on a Slovenian bank by ) The problem is that because they are not in my circle of competence, I will immediately dismiss them. It may be that I will choose to extend my circle of competence in the future(even Warren Buffett did so before considering investing in insurance), but we must remain humble, if it takes too much time and effort to understand the business, put it aside. There are 100,000 more public companies in the world out there we can invest in.I added certain companies that I do not consider on the NO-list. The reason is to check at the end of the year if I may need to expand my circle of competence or not. I try to give a short justification for why I do not consider it an investment opportunity for me.

Step 3: Quick and dirty analysis

If the idea resides within my circle of competence, I’ll look at the company by scrolling through its business model and its financial numbers.

The tool I use most often for this is Simply Wall Street. Why?

It gives you a graphical representation using the past 5 years of data

It allows you to quickly get an idea about what the company is about

It’s cheap (120 USD per year for a premium subscription)

I do not have any affiliation with the company. I just love their tools.

I’m looking for some quality indicators and running through our 100x bagger checklist.

Essentially:

Is it growing?

Is it profitable?

Is it reinvesting profits and compounding or not?

What does insider ownership look like?

What does the balance sheet look like?

If it passes the quick and dirty step, it goes towards the deep dive step. If not, the company goes on the NO list with an explanation of why it was not withheld.

In 2024, I’ll make a slight change to the process as I will also consider companies that are not profitable yet but might be in the future. These can then go further into the pipeline. This means that the above 100x checklist will not hold for these types of companies.

One specific question I added based on my annual review of 2023 is the cyclicality of the business or the industry. Is it in a downturn or not? Why? These are important questions to ask.

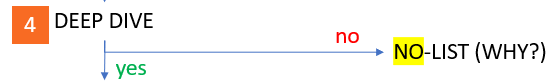

Step 4: Deep Dives

Gradually a list of companies is generated that I could investigate further. But there can be several companies in here, and we only have 24 hours in a day, so I’ll rank the companies within this list, and then start with a deep dive on those that are ranked highest. Ranking will be based on the quality of the company.

To get an idea about what a deep dive looks like, look at past articles on Inmode or Dino Polska.

Based on this analysis, it is possible that I do not consider it an interesting idea to invest in, and it goes onto the NO-list. Or we go further down the funnel.

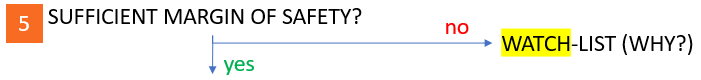

Step 5: Margin of Safety

Although this part is usually covered in the deep dive, it’s important to explicitly ask the question. Do we think the company is undervalued, and if so, by how much roughly speaking? If there is no margin, then the company goes onto the watchlist. We wait.

If there is sufficient margin, then there is a final question we need to answer.

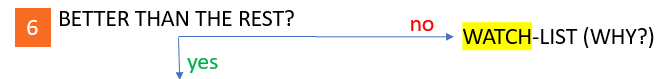

Step 6: Is it better than the rest?

Is it better than what I already own? It is worthwhile to sell an investment and replace it with this one. This is often one of the most difficult decisions. I’ll look at both deep dives and compare.

Step 7: Taking action

I’ll never buy into a company without reading its annual reports. But this doesn’t necessarily mean that I have done a full deep dive into the company and written about it yet. You only really learn about a company once you own it. So it may be that in the process of doing the deep dive, but before having finished it, I bought a first stake in the company. I’ll build the position gradually once I have done all my due diligence and through the following the evolution of the company in the next quarters.

As discussed in the margin of safety step, I prefer doing all the work beforehand, having a sound understanding of what the company does, and then lying in wait, buying only when I think the price is right. In 2023, the companies that fit this bill were:

Adyen

Dino Polska

which I both bought when their price dropped.

Step 8: Tracking the investment thesis

Portfolio management

I try to make portfolio management as simple as possible:

About 12 companies in the portfolio as I think this allows for sufficient diversification and is probably the limit of the number of companies I can track with the time that I have. A second reason is that if you own more and more companies then there are 2 possibilities:

You can pick great companies every time which I think becomes more and more unlikely

You are better off just buying an index fund

Each max position size on a cost basis is 8%. I emphasize the cost basis as I have no problem having a company growing to 50 or 60% of my portfolio (which is currently the case).

A position is built up from 1% up to 8% in a gradual manner. I only allow myself to average down once from 1 to 4%. The remainder of the position has to be averaged up. (again learnings from 2023)

I’m almost fully invested. Once I am, I’ll have to rotate, and replace my worst conviction in the portfolio with a new position. It becomes a relative game.

When to sell?

As always in investing, it depends on the type of companies I own. Each company has a set of selling rules I define before taking a position.

These selling rules are usually based on revenue growth and competitive advantages but can be more elaborate.

I’ll take 2 very specific examples:

Dino Polska: Dino is a true compounder. I do not own a full position just yet, so if the price comes back down from current levels, I might average up to a full position. I would only sell Dino if I could see disruption coming and affecting Dino’s business model. For example: Once the Polish market is more developed, a competitor has found a way to start chipping away at the market share Dino holds. We should be able to see this in Dino’s revenue growth and margins. At the moment, the market in Poland is still growing, Dino is finding more and more ways to generate revenues and profits, so in the short term, there won’t be a reason to sell.

Tinybuild: Tinybuild is a completely different story. In my article, I talked about it as a turnaround story. At the moment, it’s not turning around, it has even taken a turn for the worse, by needing to raise additional capital and diluting existing shareholders. My investment thesis was that the value locked in the pipeline of the company is much higher than the market cap of the company. However, the liquidity problems could lead to this value being unlocked because of cost-cutting or no more liquidity. The company, after having cut costs and if the capital raise is voted, will have a new injection of liquidity. Several major games in their pipeline will be released in 2024. This leads to an increase in revenue, an increase in cash position, and a stabilization of the company. The question then becomes, what of the future? My selling rules are then as follows:

If games are delayed anew in 2024, and additional cash is not flowing into the company, they might need an additional cash injection within the next 12 to 18 months. This is not a sustainable way to run a business and I may be forced to sell my position

If games are released on schedule but do not generate enough revenue to get a stable cash flow operation going, I again may be forced to sell my position

Another opportunity is available where I would have to cut my losses and invest in a new position (this is the hardest to do, but needs to be considered)

To conclude, when you buy a private company, you are forced to think of an exit strategy, as the shares you own are highly illiquid and the goal is in the end to get your investment back. It shouldn’t be any different for a public company. It’s important to define selling rules before investing and adapt these rules as you get to know the company.

The most important part of the rules is to help yourself in avoiding making emotional decisions. I could have sold my entire position in Tinybuild after the latest price drop and the announced equity raise, and maybe in a year, I might look back and should have. But based on my selling rules, I first want to have a look at the value that is locked in the pipeline. I might be wrong. Time will tell. At least, I’m trying my best to analyze the situation rationally and avoid making quick emotional decisions.

Changing the process in 2024

Based on what I have learned from Paul Andreola’s investment strategy, for 2024, I want to have a more focused approach to looking for companies mainly in the core part of the portfolio.

Just as Paul has a very specific investible universe, we’ll generate a list of companies we’ll want to look at in 2024. Here are the criteria:

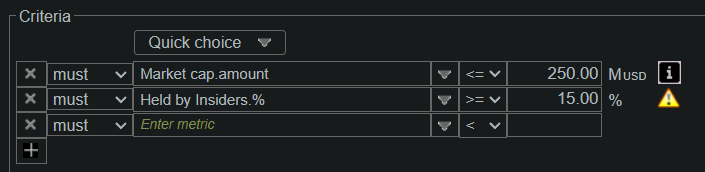

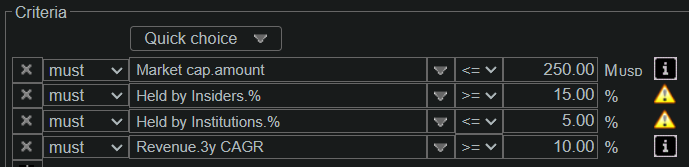

Small companies: < 250M USD market cap

Revenues have to be growing with a 10% CAGR over the last 3 years

High insider ownership of at least 15%

No or very low institutional ownership of a maximum of 5%

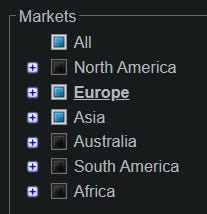

Focus on 2 geographic regions:

UK

Poland

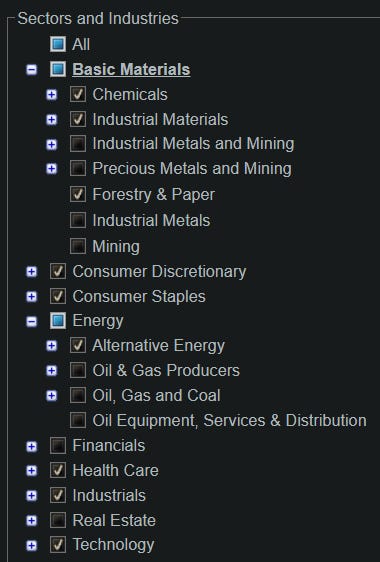

Exclude commodities, banks, utilities

That’s it. No filters on profitability, pricing in the market, or anything. The goal is to get as much raw data as possible.

The choice of the geographic regions is determined by the companies I already own. Because I’ve studied these 2 markets in the past, I want to capitalize on my knowledge and not stray into other markets I have never studied before. This comes back to having limited time and knowledge and trying to spend it efficiently.

As shown in Paul’s strategy, the goal will be to look for small companies that are growing and look for inflection points.

Because it’s a quick and dirty analysis, we’ll do 2 things:

Skim through the annual reports

Use Simply Wall Street to get a first idea of the company

I will use a screener to make a list of companies. Paul tries to gain an information edge by going upwards from the annual reports. We are going to use unclestock.com to generate the list.

First the regions: Poland, and the UK: 2776 companies

Second the industries, we exclude mining, commodities, financials, oil and gas, and real estate and utilities: 1732 companies

Now we limit the size of the company: market cap of a maximum of 250 M USD: 856 companies

We want companies with a certain insider ownership >= 15%: 568 companies

We do not want any institutional ownership = 0% but the screener does not allow you to put in 0%. If we say, less than 5% institutional ownership we get 152 results.

The last thing we want in these companies is that they are growing. Let us take a revenue growth CAGR of 10% over the past 3 years.

This leaves us with an investible universe of 64 companies. In 2024, we’ll go through this list in a series of posts called A to Z - Quick and Dirty.

31 trade on the Polish market and 33 on the London Stock Exchange. You can find the full list here.

Since we have about 10 articles planned for this in 2024, this means about 6 companies each month I’ll need to go through. The fewer people that are talking about or tracking these companies the better.

To conclude

I hope you enjoyed gaining some insight into the process I use. Looking forward to combing through that list of 64 companies and hopefully finding some gems in there.

Take care, and may the markets be with you, always.

Kevin