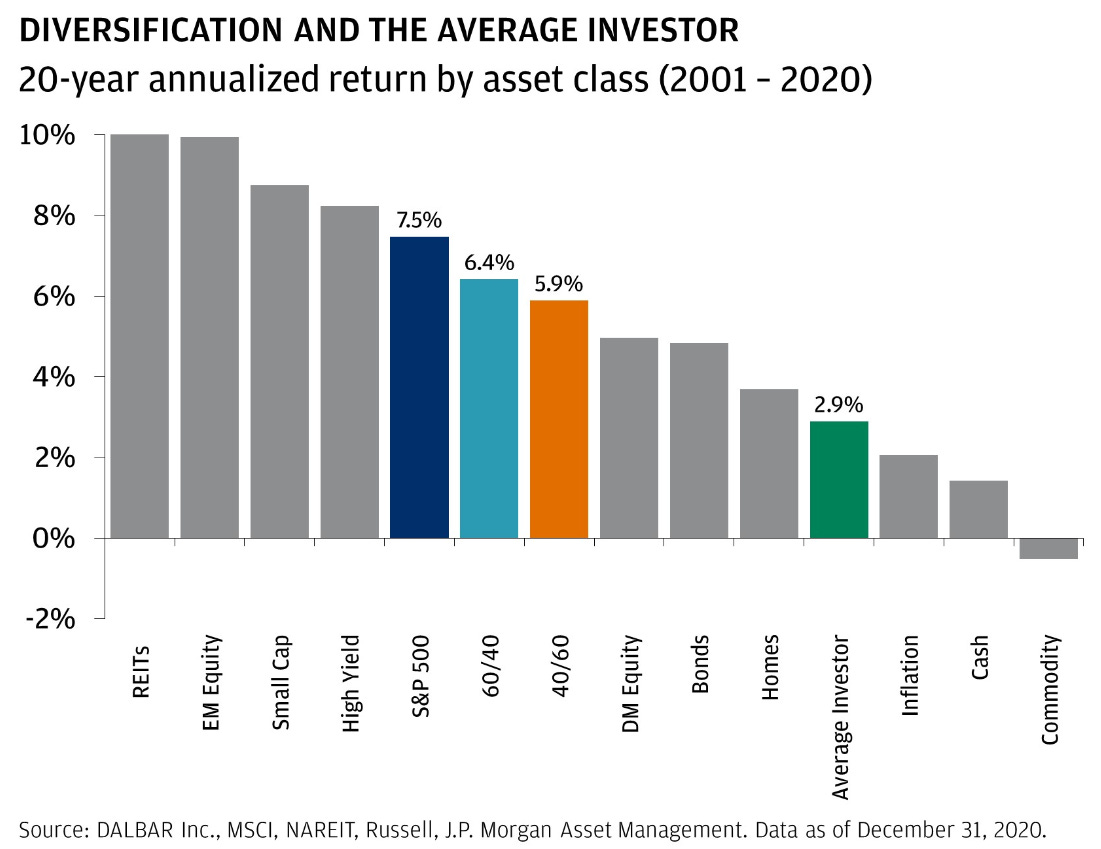

We think we act rationally in the markets, but the data proves otherwise.

You probably have already seen this graph calculated by dalbar.

It shows how what they call ‘the average investor’ underperforms most of the different assets classes because of bad timing and fees. Dalbar uses flows into funds and fees structure to get an idea of the average investor’s performance.

Although we need to be careful with these sorts of graphs, we cannot ignore that behavior and temperament play a vital role in stock market returns.

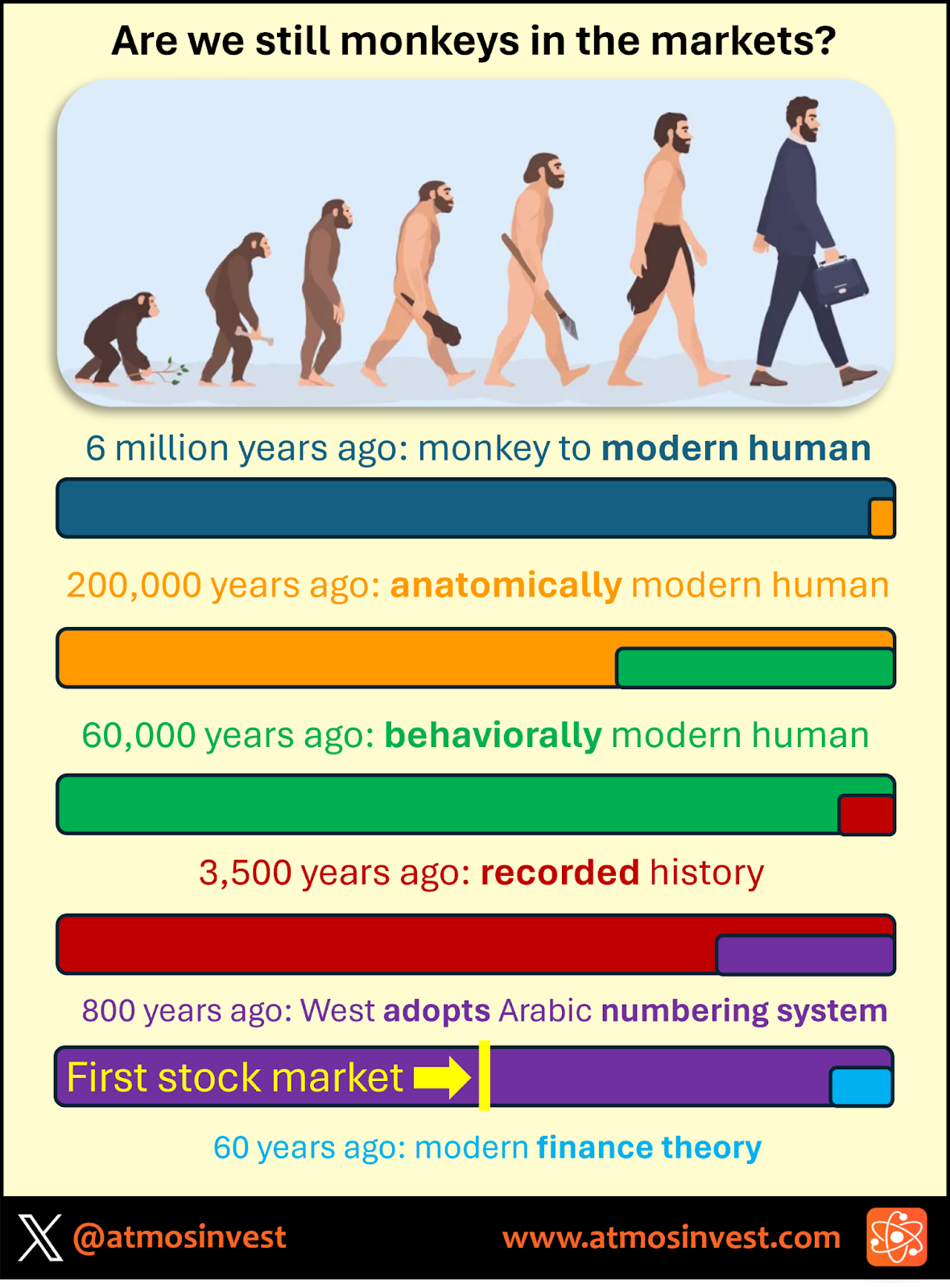

We are fighting a fight against evolution: We are equipped with a brain that has not changed over the last 60,000 years. In other words, it has not evolved to function inside financial markets.

Here’s what history looks like:

Click below to go to the full thread:

Let us zoom in on the behavioral part.

Our brain now is similar to our ancestors 60,000 years ago

We’ve started writing 3,500 years ago

Our numbering system is only about 800 years old

The first stock market was established 400 years ago (Dutch East India Company)

Modern finance theory has been around for 60 years now

It’s not surprising that our monkey brain does not help us in the markets. This quote I found in a harvard business review article says it all:

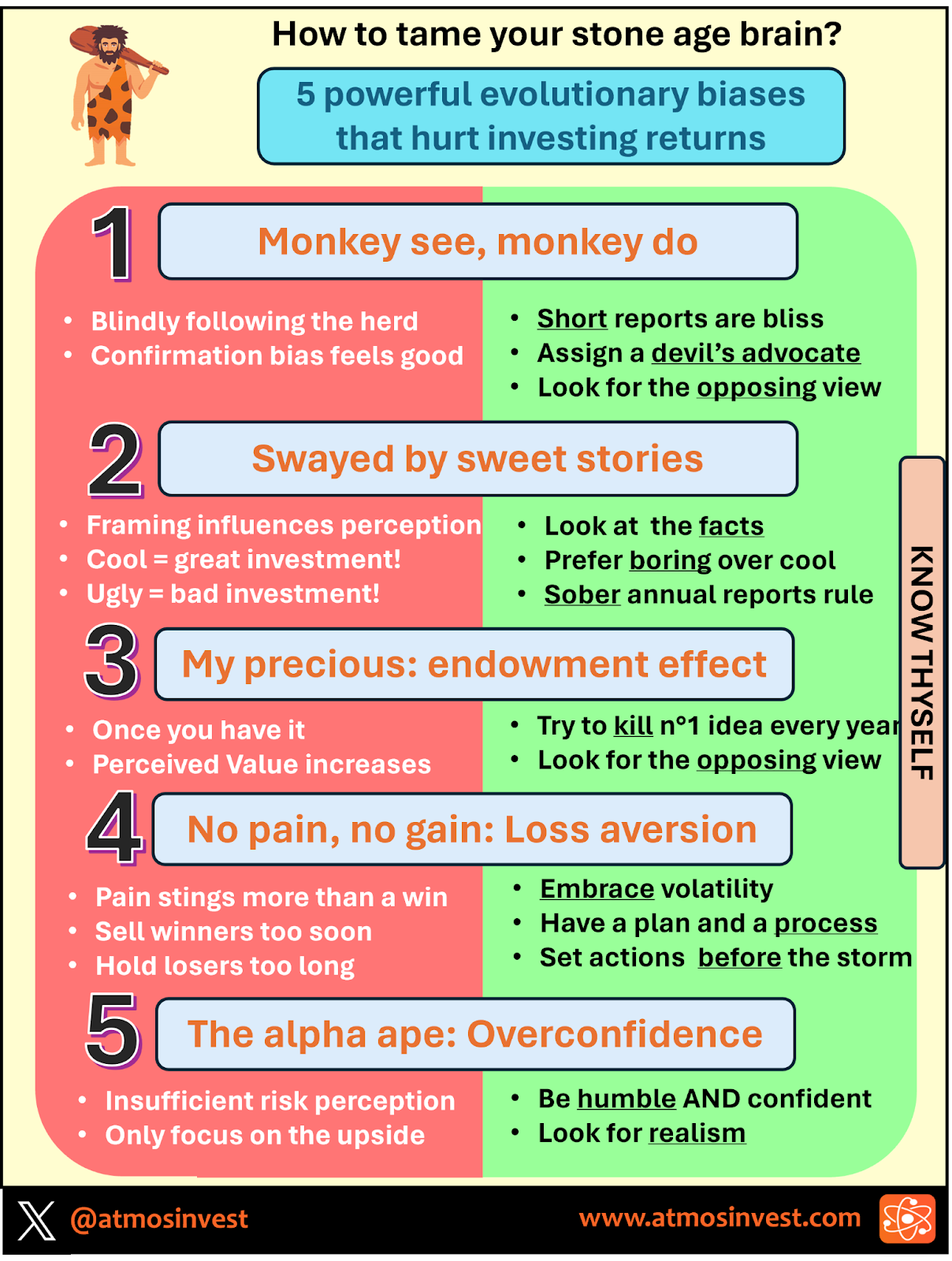

Let us zoom in on 5 biases that are great in the wild, but not so much in the markets.

I would emphasize that these biases and the necessity of a great process are important for any investor, but even more so for the small-cap investor who willfully exposes himself to more risk and more volatility.

1️⃣Monkey see, monkey do

Humans, just like other mammals, like to be part of a herd. It provides a soft warm blanket and feels good socially to be part of something bigger. This copying of others and following the crowd can be very detrimental when investing in the stock market.

Getting ideas from other investors is a good idea. But blindly copying them is not. You can clone a position, but you cannot clone a conviction. Without conviction, you won’t be able to hold on when volatility strikes, or to know when to sell.

What can we do?

Do your own due diligence, especially when the idea comes from another person

Actively look for the opposing view. If you come across an interesting company, first look for short reports or bear reports on the company. The comment section on substacks or seeking alpha articles is also a great place to look for. When someone pitches a company, you’ll usually find some pushback in the comments

Find a devil’s advocate: If you’re part of an investing group, or know other people, ask one of them to assume the role of devil’s advocate

2️⃣Our brain loves a great story

Stories have been told for ages. Before the written word, a tribe would gather around their village elder, and knowledge of the world would be transferred through stories.

But stories are dangerous. Our brain has the tendency to make stuff up. It loves filling in the gaps and being creative.

In investing, we see this commonly when price drives narrative. When a stock is in a downward spiral, most written articles will be about how poor the company is. When suddenly the company starts outperforming, it has now become the best company on the face of the planet.

How something is presented, framed is crucial. When the same data is presented in a positive way, we have a tendency to see it as interesting. Take that data and present it in a negative way, and it becomes far less appealing.

Form matters.

What can we do?

Be mindful in what order you’re processing an idea. Don’t start reading that deep dive from the start. Once the idea is there, start by reading the annual report, and try to kill the idea. If you’re unable to kill it, deepen your due diligence. Only later start reading the full story deep dives of others.

Be skeptical of how information is presented by management. The less flashy a presentation or the more boring an annual report, the better

Ignore price from the start. The narrative should be guided by the performance of the company, not by its price in the market. Pricing and valuation can be done at the end.

Look at the facts

Boring = cool

3️⃣No pain, no gain: loss aversion

Prospect Theory dictates that choice of risky prospects is based on change in wealth. In this change, a loss is more painful than the joy of a win.

The origins could be traced back to evolution: The need to maximize the number of offspring shows a similar relationship and also leads to loss aversion.

The impact on our returns can be catastrophic: Selling our winners too soon or holding on to our losers too long. Volatility in the markets plays an important role in this.

Remember:

What can we do?

Have a plan and a process in place

Define actions to take when things go sour, before the storm comes

Embrace volatility. Volatility does not equal risk. It can be an ally.

4️⃣The alpha ape: Overconfidence

In the stone age, being confident was important as it could lead to more status, being perceived as more attractive to mate.

This overconfidence is ingrained in our brain and permeates everywhere.

Too much focus on returns instead of the downside risk

Overestimating base parameters when valuing a company

Overestimating what the future will look like and ignoring base rates

This leads us to a paradox.

The solution is to be humble and confident at the same time. Humble to always keep learning and consider yourself wrong in your thesis. But confidence is needed in your own analysis in order to make that buy decision.

What can we do?

Be humble and confident

Look for the truth, look for realism

5️⃣The endowment effect

I held this one for last, because it’s an important bias to be aware of, but in fact there are contradictory articles to conclude if this one is actually related to evolution.

In one study, they have studied the endowment effect on the last isolated hunter-gatherer tribes that still live on the earth today. Their conclusion was that only when they were exposed to items and markets, that the endowment effect took effect.

This might come down to possessions. A nomad or hunter-gatherer, by definition, does not have a lot of stuff. Once you flip into the agricultural phase, and people start to accumulate, the endowment effect becomes stronger.

Another study observed the behavior of capuchin monkeys. Here, when elements of trading (they taught the monkeys how to trade coins for food) the endowment effect was observed implying a possible evolutionary link in the brain.

What can we do?

We can bow to the wisdom of late Charlie Munger: Try to kill your best idea or holding each year

Actively look for the opposing view to try to detach yourself from your ideas

Summary

There are several other biases out there, but I refrained myself from looking only into these 5 powerful ones.

But when all is said and done, the most important thing we can do is inscribed on The temple of Apollo in times of ancient Greece. You need to tilt your head 90° to read it (or your computer our phone).

I’ve focused more on the process of investing over the last 2 weeks. Next week, we’ll dive back into microcaps. The week after, a multi-bagger case study will come up.

As always, may the markets be with you

Kevin

Further reading

Greats books/podcasts on behavioral finance

Excellent podcast by The investor network with Gary Mishuris

Thinking fast and slow by Daniel Kahneman

Misbehaving: The making of behavioral economics by Richard Thaler

The emotional intelligent investors by Ravee Metha

Great write-ups on the topic

Excellent article from Gary Mishuris:

And another one I liked on cognitive errors:

Great line - "You can clone a position, but you cannot clone a conviction."

Unexpected read but I loved it!

Great subject to read/ learn about. Good stuff